Sarah Harte: Every generation seems to have its Cuban missile crisis — Is this ours?

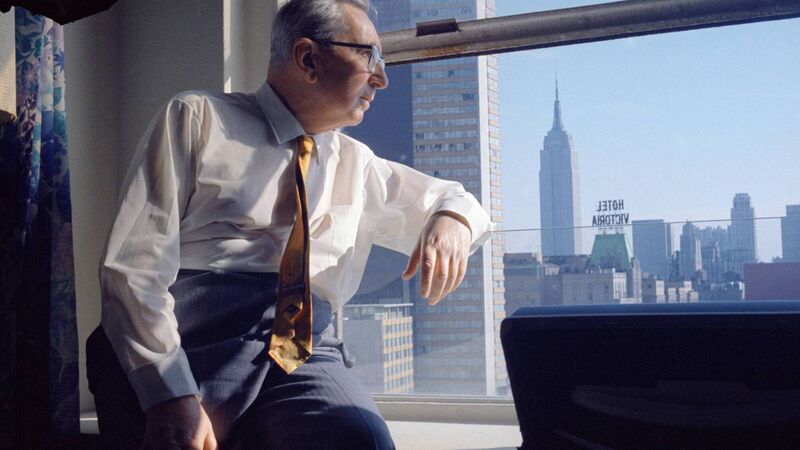

Austrian psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl in New York in 1968. He wrote: 'The last of the human freedoms — to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.' Picture: Imagno/Getty Images

Albert Camus wrote in his essay : “To decide whether life is worth living is to answer the fundamental question of philosophy. Everything else… is child’s play; we must first of all answer the question.”

There are times when, even if you are an optimistic person who automatically looks for the bright side, that impulse fails.

Last week, I got to Friday feeling like I had been waterboarded. Each day brought a fresh challenge. There’s a part of your brain that recognises being overcome, but you think: “What right do I have to get upset when others have far more significant struggles?”

I’m unsure, though, whether the concept of comparative suffering is particularly helpful.

A Cork GP once told a teen friend of mine she should be ashamed of herself for being upset about her bad, persistent acne (which pockmarked not only her skin but her life for a prolonged period) when children were starving in Africa. It stayed with me.

However, sometimes you come across a person whose outlook stops you in your tracks. Driving into Skibbereen on Friday evening feeling crushed like a bug, I heard an interview on Drivetime.

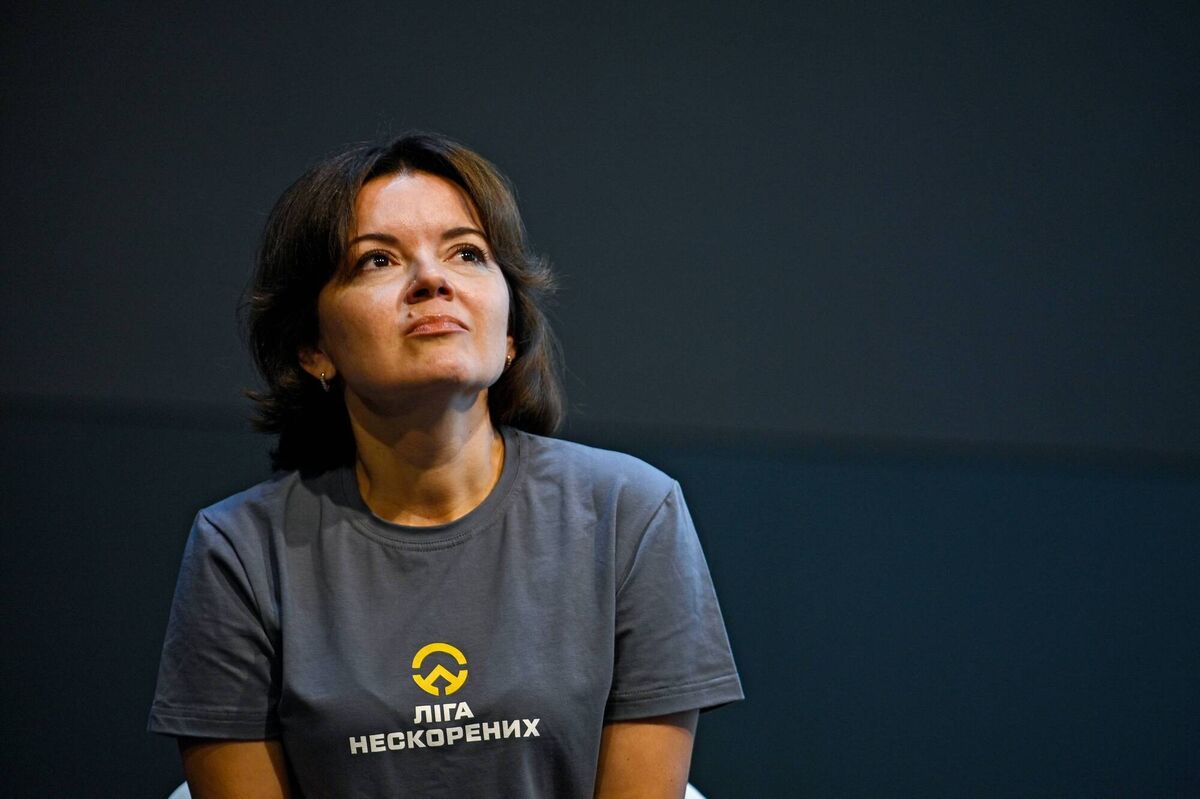

Katie Hannon interviewed journalist Marichka Padalko, well known in Ukraine as a television anchor and feminist.

Ms Padalko was one of the first journalists to report on the 2022 Russian invasion. Her interview with Katie Hannon was remarkable.

It’s hard to describe how philosophical Ms Padalko is. Her bravery was humbling.

Her husband, Yehor Soboliev, a Ukrainian politician, has been on the frontline for four years.

Her son, who completed one year of university, is now also on the frontline. She is proud of him. I think the idea of a son being on the frontline would strike unspeakable fear into the breast of most mothers. She made the point that if she thought about it, she would go crazy.

She sent her two daughters to Czechia, but they returned to Kyiv because they wanted to come home.

She recounted that they were lucky because they had a gas heater and could wash.

On the left bank of Kyiv, people weren’t so fortunate.

Hours after that Drivetime interview, thanks to intense Russian bombardment, 1.2m people were left without power in Kyiv while temperatures hover around -10C.

The Russians are trying to freeze the Ukrainians to death by hitting their heating systems.

Ms Padalko’s family no longer goes to bomb shelters because, after four years of war, they just can’t keep doing that. So, when Katie Hannon asked her about the risk they were taking, she said there was a black Ukrainian joke: “You wake up, you go to work, you wake up dead, you don’t go to work.”

Ms Padalko talked about having social gatherings in a work context where there was heating from generators, and where they (not her exact words) went on defiantly.

That is remarkable in itself under those circumstances; to get together and spark joy in others.

Listening to Marichka Padalko makes you wonder about the absolute courage and resistance against the worst excesses of our fellow man and, simultaneously, what we are capable of doing to each other.

At the weekend, I watched the footage of the latest fatal ICE shooting, this time of an intensive care nurse in Minnesota, and I thought, what do the actions of these goon squads, comparable to the Black and Tans, signify?

Watching a BBC Verify video of the shooting slowed down frame-by-frame, it’s clear that Alex Pretti had a phone in his hand, not a gun.

Alex Pretti's gun, which was legally held, was in his waistband and removed by a Federal agent after they restrained him on the ground.

They then shot him, unarmed, several times.

How to calibrate that? Or the bravery of his nursing colleagues and the many other protesters who came out to stand on the frigid streets of Minnesota with a wind chill of -20C, with cardboard signs reading ‘Justice for Alex’. Ordinary men and women who are taking a significant risk under these febrile conditions.

Their actions have been described in some quarters as acts of historic bravery. Protesters included faith leaders singing hymns and businesspeople who shuttered their cafes and shops to pause everyday activities.

The fortitude of humans to go on in the most awful of circumstances — the ability to retain a kind of tempered hope and a shining, brave dignity — makes you feel a bittersweet joy about what it means to be human.

Ms Padalko’s mindset reminded me in some ways of celebrated psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl, who ended up in Auschwitz and other Nazi death camps where his father, mother, wife, and brother died.

He rejected an “end-of-the-world” mindset. His book, , giving an account of his experiences in Nazi death camps, offers profound insights into human resilience.

Both Ms Padalko and Mr Frankl seem to ask us to find meaning in a world that offers endless reasons to believe life is worthless.

We can admit that the current backdrop to our lives, running like a film, is continually jolting.

And yet, fearmongering is unhelpful.

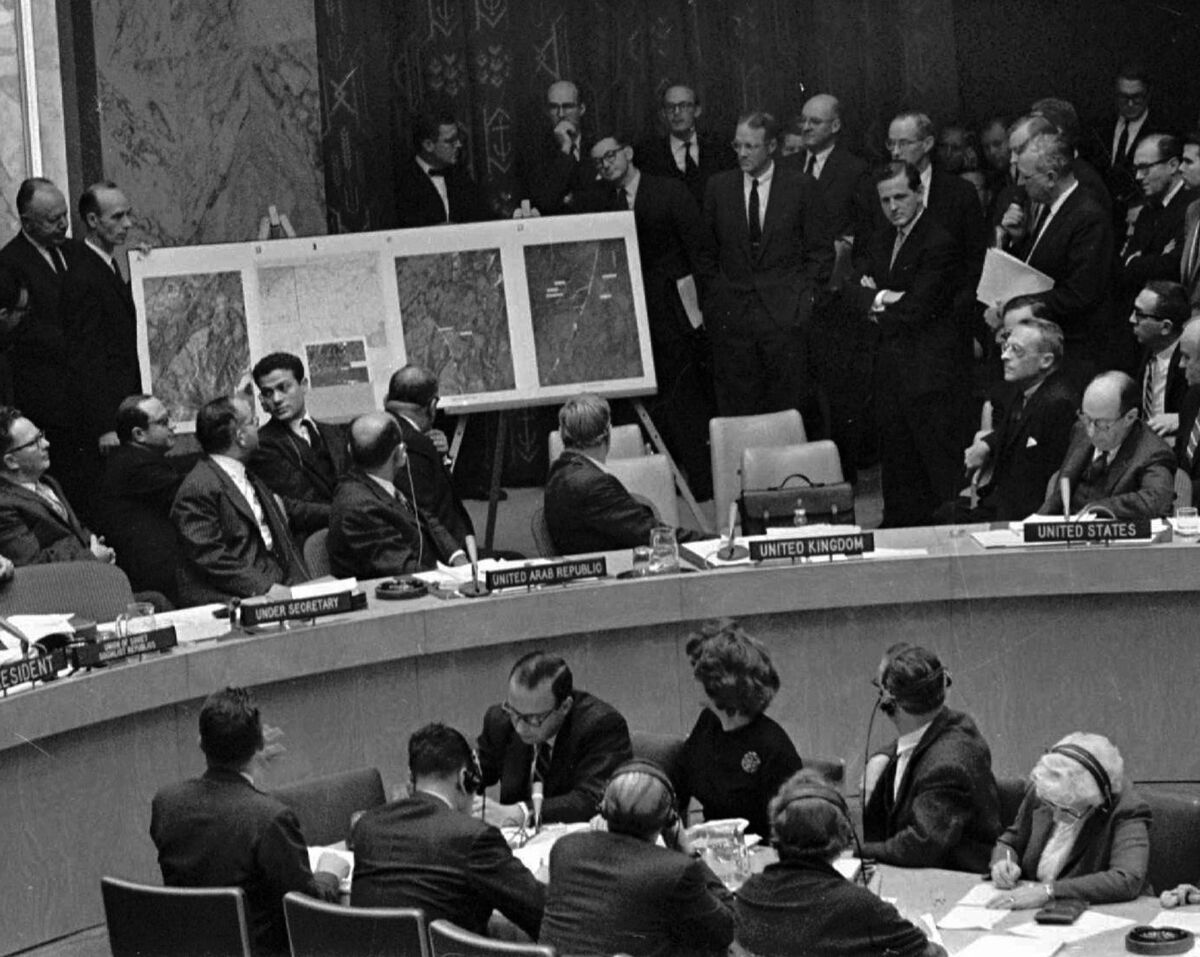

Might we also have a collective tendency towards amnesia? Did our grandparents’ and parents’ generations not experience the Cuban missile crisis after the failed CIA-backed Bay of Pigs invasion to overthrow Fidel Castro’s regime?

The confrontation was considered the closest the Cold War came to escalating into full-scale nuclear war.

Maybe this is reaching for a comfort blanket, but could it be another example, one of many, of how the gauntlets thrown down to us differ from life to life and also from epoch to epoch?

But how do you personally compare your piffling problems to the scale of those challenges? Should you feel ashamed? Of course, you must retain perspective, but we all inhabit our mental universe for better or worse. Nobody wants a meltdown, but you have a right to your emotions, and it’s OK to acknowledge tough times or fears.

Viktor Frankl had an interesting take on comparative suffering.

“The question life asks us, and in answering which we can realise the meaning of the present moment, does not only change from hour to hour but also changes from person to person: The question is entirely different in each moment for every individual.”

Despite challenges that sometimes feel insurmountable, every single day counts. Our time is finite, and we have a responsibility to make the most of our lives.

I’ll leave you with one last inspiring thought from Mr Frankl, which was part of his core philosophy and could be called a coping strategy.

Everything can be taken away from us except one thing: “The last of the human freedoms — to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

I might print it out and tack it to the wall.

Listening to Marichka Padalko makes you wonder about the courage and resistance against the worst excesses of our fellow man

• You can listen back here on RTÉ.ie to Katie Hannon's interviews with John Everard and Marichka Padalko