Paul Hosford: Politicians should be able to question the use of the Special Criminal Court

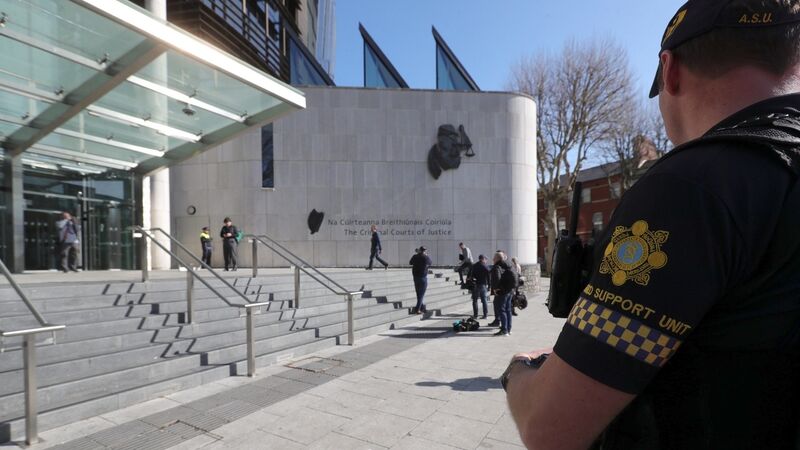

High security at the Special Criminal Court in 2023 for the murder trial of Gerry “The Monk” Hutch. The court has been operating on an ‘emergency’ basis for 50 years, traditionally dealing with terrorist offences, but, in more recent times mainly concerned with organised crime. File picture: Collins Courts

A future presidential candidate once wrote of the Special Criminal Court: "It is a precondition to the lawful establishment of Special Courts that the ordinary courts are found to be inadequate, and a condition of their validity that this inadequacy continues throughout the duration of such Special Courts.

"This places a burden of responsibility on the Oireachtas to monitor the situation closely, and to determine from time to time whether in fact the ordinary courts are still inadequate for the administration of justice in certain circumstances. At the moment the Oireachtas shirks this responsibility