Gareth O'Callaghan: Finding purpose and meaning in life is where we must all begin

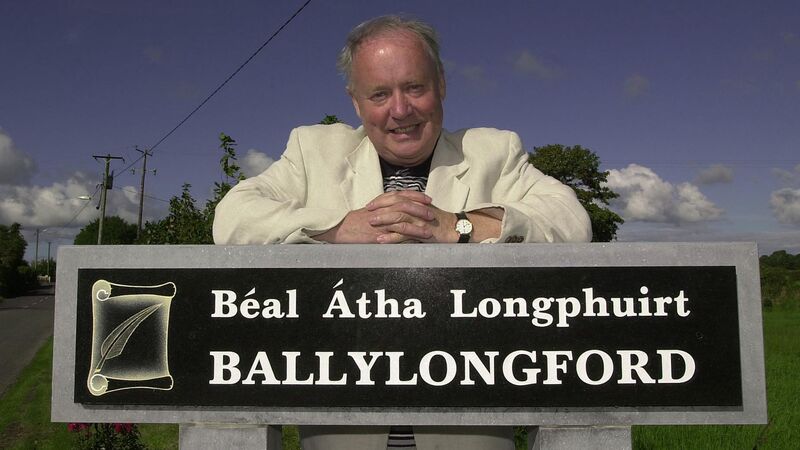

Brendan Kennelly was one of the country’s most popular poets and a former professor of English at Trinity College Dublin.

Some years back, I fell in love with poetry. Books of poems by Seamus Heaney, Mary Oliver, Wendell Berry, and others take up space on my bookshelves, and in my travel bag for my train journeys.

However, my favourite poet over the years has been Brendan Kennelly, the roamer and raconteur. Kennelly hailed from Ballylongford in County Kerry. He was a professor and lecturer in Modern Literature for many years at Trinity College Dublin.