Alison O'Connor: We must not let fear of litigation halt future screening programmes

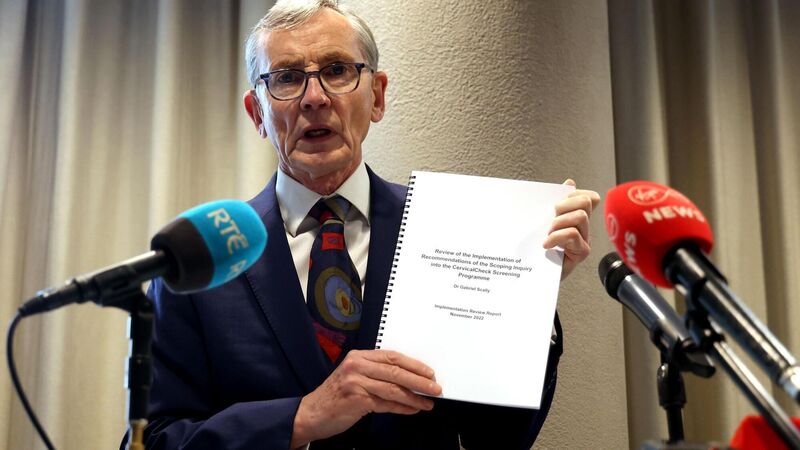

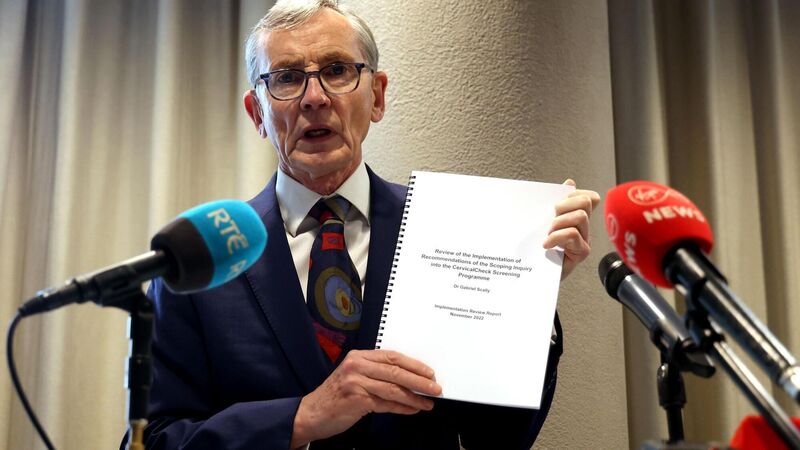

Gabriel Scally stated: ‘Women can have confidence in and should take full advantage of the cervical screening programme.’

Try from €1.50 / week

SUBSCRIBE

Gabriel Scally stated: ‘Women can have confidence in and should take full advantage of the cervical screening programme.’ Picture: Sam Boal

A Government establishes health screening services to protect its citizens on a population-wide basis. Despite being screened, some citizens still get cancer. They blame the State. They seek large amounts of compensation. Now the very existence of those programmes comes under threat, and the State thinks twice about setting up new ones. It’s a cautionary tale.

This week, Gabriel Scally finally signed off on his examination of CervicalCheck, saying there is now a screening service that women can trust, that has improved substantially. The many recommendations he made in his 2018 report have been substantially completed.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

You have reached your article limit.

Annual €130 €80

Best value

Monthly €12€6 / month

Introductory offers for new customers. Annual billed once for first year. Renews at €130. Monthly initial discount (first 3 months) billed monthly, then €12 a month. Ts&Cs apply.

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates

Newsletter

Sign up to the best reads of the week from irishexaminer.com selected just for you.

Select your favourite newsletters and get the best of Irish Examiner delivered to your inbox

Sunday, February 8, 2026 - 5:00 PM

Sunday, February 8, 2026 - 6:00 PM

Sunday, February 8, 2026 - 1:00 PM

© Examiner Echo Group Limited