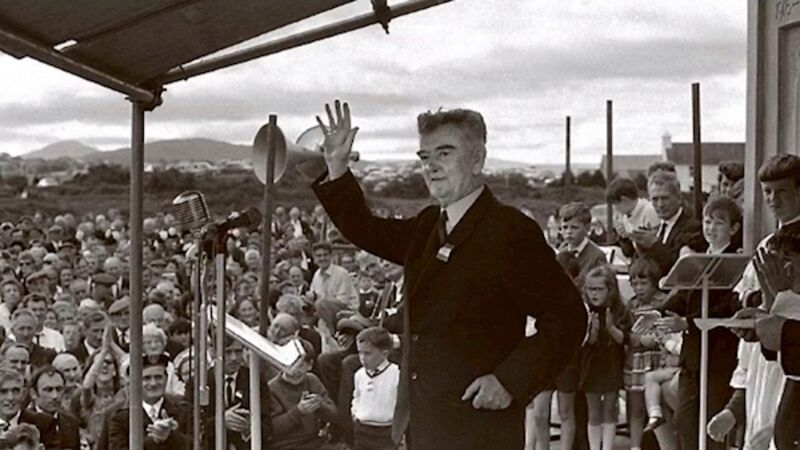

Unpalatable truths can’t be waved away

The past is upon us again. On Monday, the second phase of centenary commemorations begins.

The first phase, those events commemorating 1916, went off without incident and was largely applauded for the manner in which it was handled.