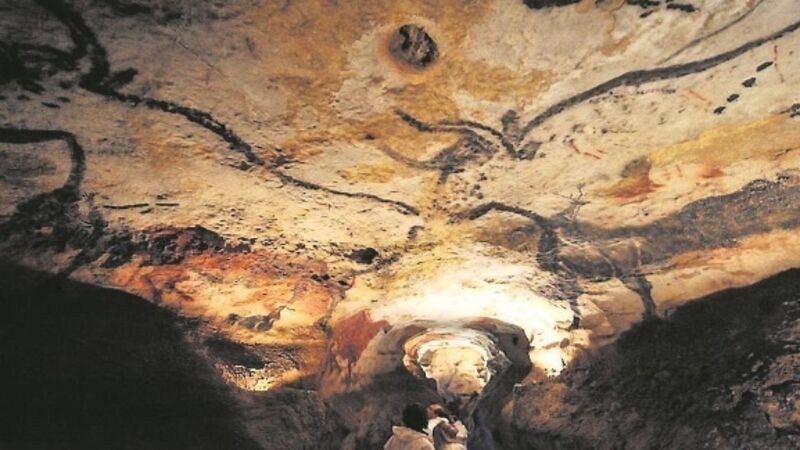

Shedding some light on cave mysteries holding stunning art created by early Europeans

In the case of caves, indoors is outdoors, and my outdoor resolution for 2017 is to visit at least three or four of the remaining accessible caves in France and Spain that contain stunning works of art created by early Europeans.

I will enjoy not only the beauty of the paintings but the wonder of them, along with the adventure of entering a world of prehistory where bisons and elks charged across landscapes and the human ambience was stone.