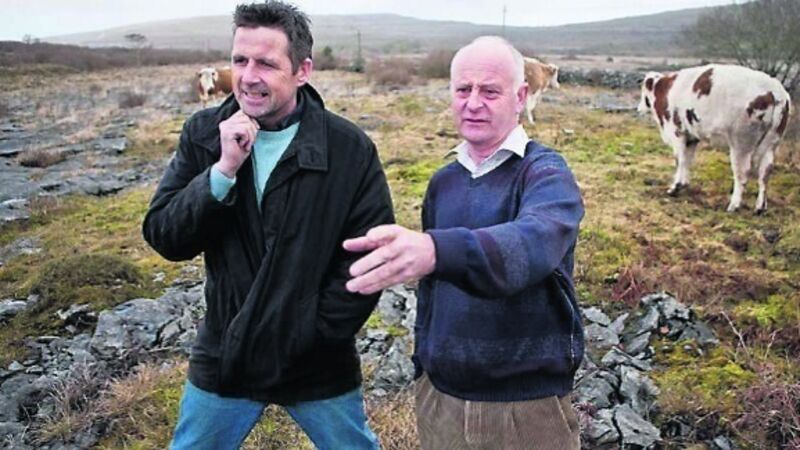

Burren land use of benefit to locals

CLIMATE change is thrusting the issue of farming and the environment into the public arena more than ever before, nearly always controversially.

However, there are age-old practices which show that people can farm and protect the environment at the same time.