Shaping the future - The more things change ...

That we do not always succeed is just another sign of our human frailty. It is natural as we, say, try to change to a healthier lifestyle that we try to forget the excess of Christmas, maybe pretend that the St Stephen’s Day breakfast of ham and trifle was just a figment of our holiday-fevered imagination. We may psychologically block out the indulgence but the evidence, sadly, is undeniably on the waistline.

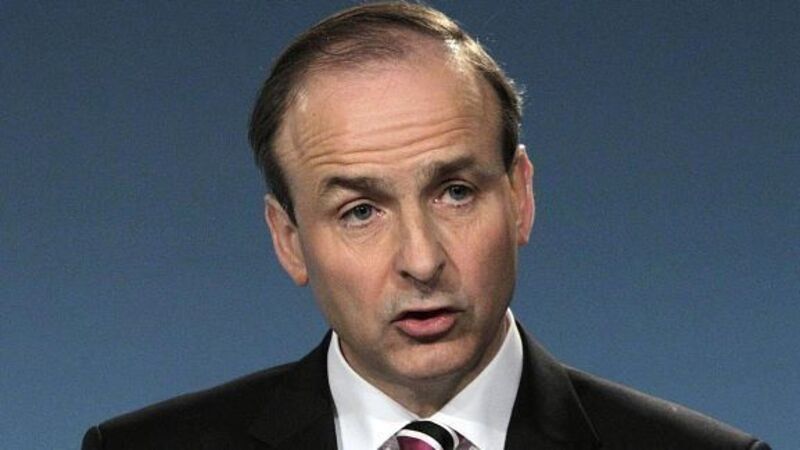

It is hard not to think that Fianna Fáil leader Micheál Martin is not indulging in a very selective review, a psychological purging as it were, of our recent history when, in an interview with this paper today, he asserts his party is no longer a toxic brand and is “moving on”.