Rights versus responsibilities — which should have priority or should they co-exist? And since the end of World War II has there been an imbalance in favour of rights, an imbalance that has segued into a distorted view of social relationships?

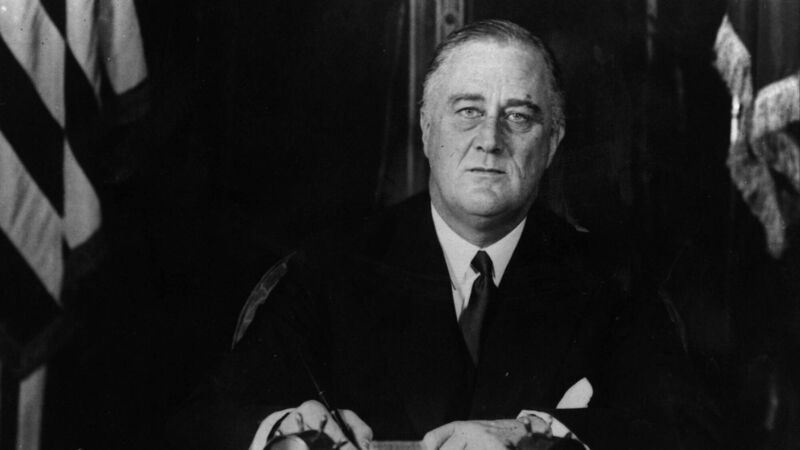

These questions have come into sharp focus following the recent Reith Lectures on BBC Radio 4, lectures that explored the implications for 21st century living of an important speech by an American president.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

You have reached your article limit.

Subscribe to access all of the Irish Examiner.

Annual €130 €80

Best value

Monthly €12€6 / month

Introductory offers for new customers. Annual billed once for first year. Renews at €130. Monthly initial discount (first 3 months) billed monthly, then €12 a month. Ts&Cs apply.

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates