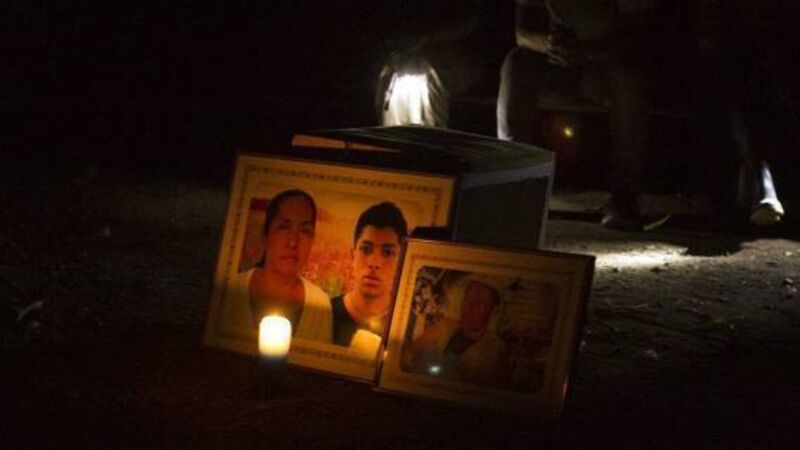

Colombia: ’Why did they kill my son, take my husband away?’

THE place where Manuel Ruiz and his youngest son disappeared throbs with the sounds of bird calls and insects.

Only the occasional struggling vehicle intrudes on the rhythm, creaking over the bumps and dips of the dirt road, engine panting in the intense heat.