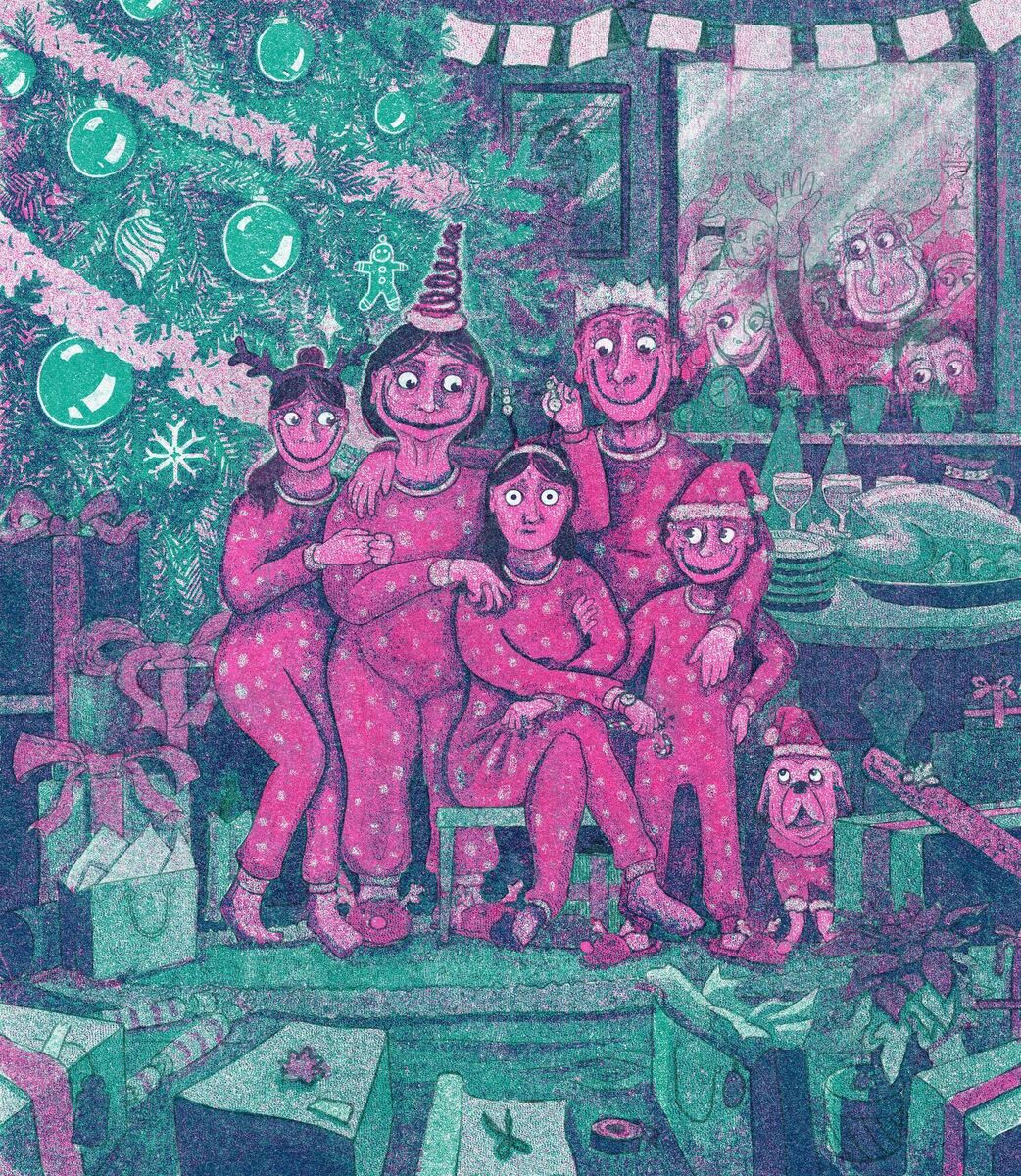

Is guilt the driving force behind an authentic Irish Christmas?

Guilt may not be a word many associate with Christmas, but in Ireland, it may as well be printed on the wrapping paper.

Guilt may not be a word many associate with Christmas, but in Ireland, it may as well be printed on the wrapping paper. It’s part and parcel of any good celebration – the invisible guest no one invited that shadows you all season long.