'Let them all die': A century on from Ireland's biggest hunger strike

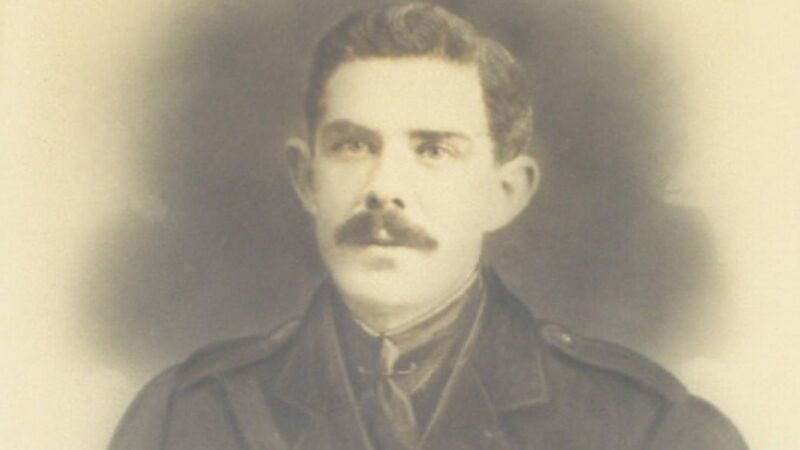

Denis Barry, from Riverstick, died on 20 Nov. 1923, after refusing food in Newbridge Internment Camp (Wikipedia)

That was the promise sworn by over 8,000 prisoners in Ireland, 100 years ago.