'I used to know a man who was in the Famine': An extract from John Creedon's new book

John Creedon with his book 'An Irish Folklore Treasury'. Picture: Larry Cummins

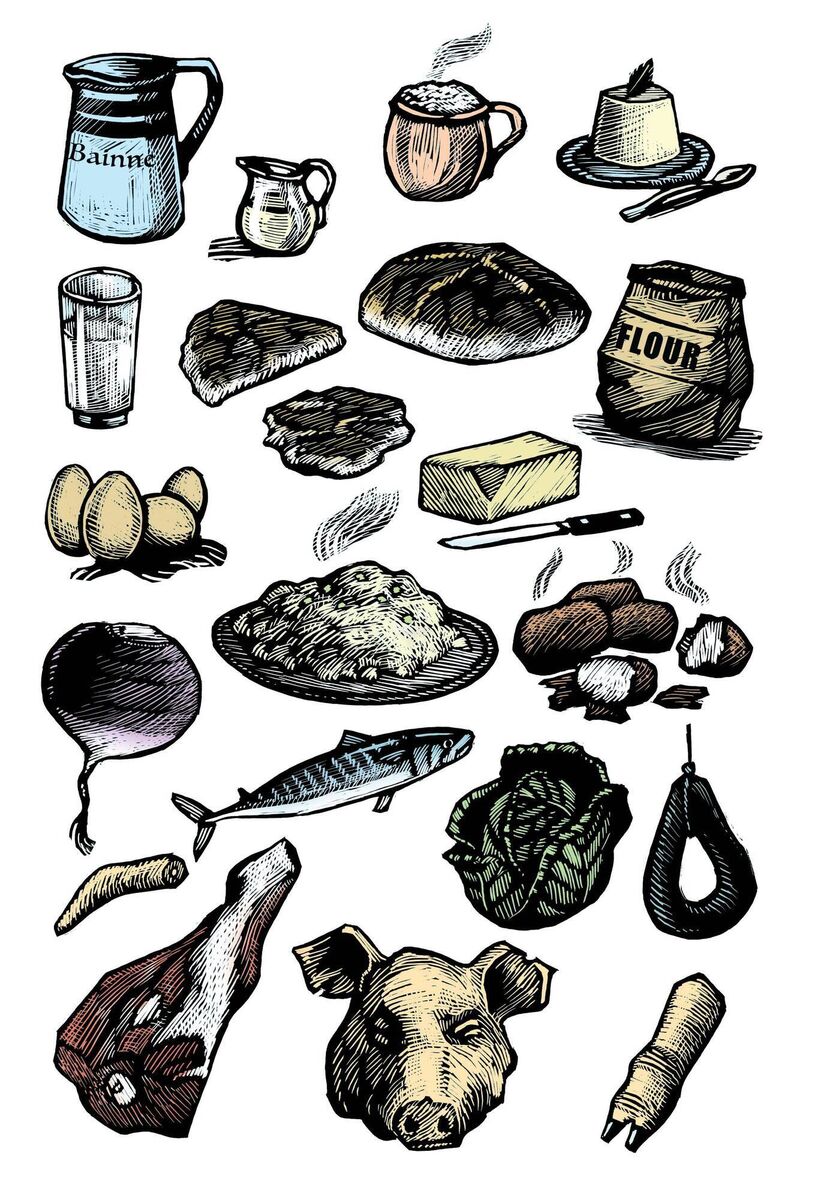

The Inuit are reputed to have 50 words for snow. The Irish had 50 recipes for spuds. A pinch of salt, a spoon of sugar, a splash of milk or a fist of flour would transform the humble spud into boxty, pandy, griddle cake, farls, and a huge range of recipes, new to me. Young Eddie Carroll of Derrynahinch, Co Roscommon, notes the sweet and sugary flour-based ‘flummery’ and the savoury ‘scailtín’.

(School: Droichead na Ceathramhna, Derrycashel, Co Roscommon. Teacher: S. Pléimeann. Collector: Eddie Carroll, Derrynahinch, Co. Roscommon. Informant: John Gildea, 57, Derrynine, Ballyfarnon, Co Roscommon)

Long ago the people used to take three meals a day — breakfast, dinner and supper. Before the breakfast the people would do two hours’ work; then they would take a basin of porridge and a can of milk and eat it with wooden spoons. Then they would take potatoes and buttermilk and sometimes they would take ‘scailtín’, which consisted of flour, onions, pepper and salt all boiled on milk and water. They used to take porridge for the supper or sometimes meal-bread or oatmeal cake. The oatmeal cake used be made with oatmeal and wet with water and then baked on a tongs. The young children used to take ‘flummery’, which was flour boiled on milk and sweetened with sugar.

(School: Clochar na Trócaire, Navan, Co Meath. Teacher: An tSr. Concepta le Muire. Collector: Eileen Watters, Flower Hill, Navan, Co Meath. Informant: Mrs. Watters, 45, Flower Hill, Navan)

Long ago the people had no tea. They used to take porridge for their breakfast and supper, potatoes, bacon and cabbage for their dinner and often potatoes for supper.Very seldom meat was used only on special occasions, at Christmas, Easter and on big feasts. Long ago they used to have cakes made of wheaten meal. The people used to make oaten bread before they set sail for America and take it with them. The table was usually placed in the centre of the floor. The people used to go to work before breakfast in the mornings and come home for breakfast.

An Irish Folklore Treasury: A selection of old stories, ways and wisdom from The Schools’ Collection is published by Gill Books, price ¤24.99