6 of Ireland's greatest archaeological discoveries

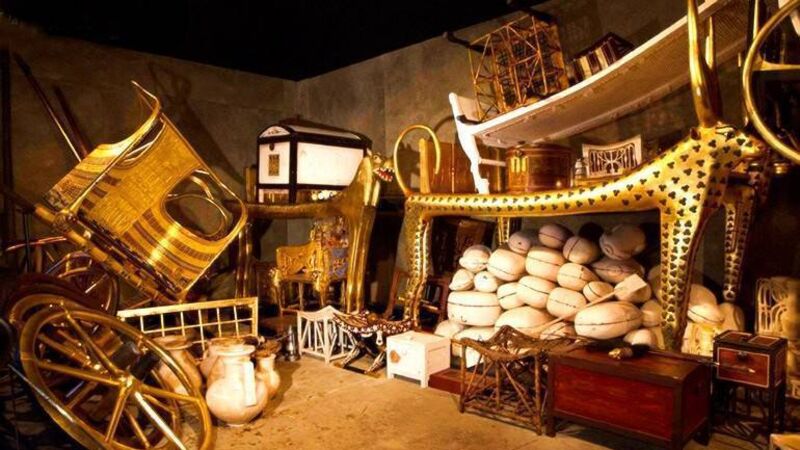

The glistening treasures in Tutankhamun's tomb

'Tut mania’ is about to grip the world once again, it being 100 years since the boy king's tomb was discovered.

Now seems like a timely moment to review some of Ireland’s wonderful archaeological finds from booty from the Spanish Armada to decapitated wannabe kings and priceless gold deemed 'rubbish' by petty thieves.

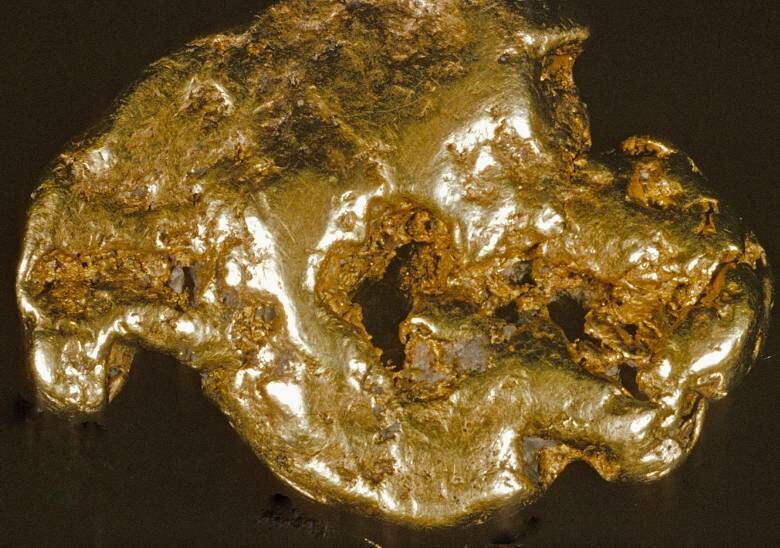

In September 1795, a gold nugget weighing 682g was pulled from the River Aughatinavought at the foot of Croghan Kinshela Mountain near Arklow, Co. Wicklow.

The sensational discovery led to a “gold rush” in this quiet river valley. Families carrying sieves and skillets headed for Goldmines River, until there were so many diggers that the Kildare militia was ordered to repossess the area.

News eventually reached London. When King George IV visited around 1820, a poor local farmer supposedly handed him the gold nugget he had found. The man had planned to sell it and start a better life, but the king graciously thanked him, and slipped it into his pocket.

La Girona sank after striking rocks on the night of October 26, 1588 near Dunluce Castle, Co. Antrim.

Only 9 of the 1,300 sailors on board survived. The wreck lay undisturbed until 1967 when Belgian diver Robert Sténuit and his team made the “discovery of a lifetime” in the murky seabed — not merely a Spanish Armada ship, but a long-lost haul of treasure.

With no authority to undertake the search, the team told locals they were filming “the underwater eco-system around the Giant’s Causeway”.

However, when they were spotted hauling out a large cannon, “there was pandemonium… the evening newspapers printed ‘GOLD’ across the front page… we were overwhelmed by tourists”, said Sténuit.

Among the hundreds of gold and silver coins, precious stones and jewellery appeared the stunning brooch, soon to be known as the ‘Girona salamander’.

After two thieves robbed Sheehan’s Pharmacy in Strokestown, Co. Roscommon in 2009, they dumped the safe, with its “worthless” contents, into a skip in Dublin.

Little were they aware that inside lay hidden a 5,000-year-old gold necklace: “Those thieves missed out big time when they unknowingly threw this treasure away”, said National Museum of Ireland’s Tony Candon.

The 78g jewel, comprising a gold crescent moon-shaped collar with two gold discs, had probably belonged to an early king of Ireland.

In 1945, Hubert Lannon gave the necklace to Strokestown pharmacist Patrick Sheehan, after discovering it when cutting for turf in nearby Coggalbeg. Since then, Sheehan had treated it as a family heirloom.

In June 2013, workers laying concrete in a fire-damaged watering hole in Carrick-on-Suir made an astonishing find.

As they were lifting old floorboards at Cooney’s bar one routine Monday morning, a line of gleaming coins caught their eye. One worker dismissed them as “useless” and flung a fistful to the ground. But when his mates cleaned them up, they counted 77 guineas and four half-guineas, dating from 1664 (Charles II) to 1701 (William III).

All in “fantastic” condition, they were minted in Britain using West African gold, and amounted to over five years’ wages for an agricultural labourer.

In February 2003, the remains of Clonycavan Man “dropped off” a peat-cutting machine in Co. Meath.

Some 2,300 years before, the poor man had been chopped in half and decapitated, his skull punctured, and his nose split open.

His hair, twisted mohawk-fashion over his head, was held in place with pine resin gel. Three months later, the torso and arms of another young man showed up 25 miles away, in Co. Offaly.

Two metres tall, Old Croghan Man was a giant. His body, with its manicured nails, was so well preserved that a murder investigation was launched.

Both men, believes Eamonn Kelly, National Museum of Ireland, were “failed candidates for kingship”. Before being killed and placed in bogs, their nipples had been cut, making them “incapable” of ruling.

In 2011 Tullamore turf cutters gasped at the sight of a strange keg seven feet underground. Cutting it open with a spade, they found inside a whopping 45kg of butter.

Bogs were ideal for preserving perishable food before modern refrigeration. But as the fat in the butter gradually decomposed, it took on a hard, yellowish-white texture, and emitted a cheesy smell.

Bog butter has been deposited in Ireland for over 4,000 years. The butter kegs were possibly offerings to the gods or a way of protecting a valuable resource, says Jessica Smyth, UCD School of Archaeology.