Ancient honeyhunting practice continues

Recreational honey-hunting with honeyguides in the Kingdom of Eswatini. Illustration by Carissa Gagashi

You scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours — proverb

Insects, carrying pollen from flower to flower, receive a delicious meal of nectar for their trouble.

Clownfish clean the skin of anemones, whose lethal tentacles protect the fish from predators.

While such ‘mutualist’ relationships are common in Nature, a most unusual one evolved in Africa and India... boys herding livestock cooperate with honeyguides to raid bee colonies for honey and wax.

The greater honeyguide — a yellow-brown starling-sized bird distantly related to woodpeckers — has a penchant for beeswax. Raiding bee-nests, however, isn’t on; the bees would soon despatch a bird foolish enough to try doing so.

Did you know there is a bird that guides humans to wild honey?

— Wikipedia (@Wikipedia) October 12, 2024

The aptly named “greater honeyguide” leads several eastern and southern African Indigenous groups to bees' nests. After people harvest the honey, the bird feasts on the leftovers.

Birds like the honeyguide have… pic.twitter.com/QQ7qGQ26C1

But there’s a mammal which likes to gorge itself on honey. The ratel, once thought to be a type of badger, is a large dark-coloured rather ghoulish-looking creature. Its bite, it is said, renders a person infertile. Accomplished diggers, ratels were accused of plundering graves and eating corpses in India during the days of the ‘Raj’.

Bee stings don’t penetrate the honey badger’s skin, so it can attack bee-nests at will. But finding nests to raid is a challenge. Although the relationship has not been demonstrated scientifically, honeyguides and ratels are believed to cooperate in doing so. The bird locates a nest and, using distinctive calls, leads a ratel to it. The ‘honey-badger’ then climbs up to the nest, which is usually in a tree-hole. 'Rape and pillage' ensues. The bird is rewarded in left-over wax for its services.

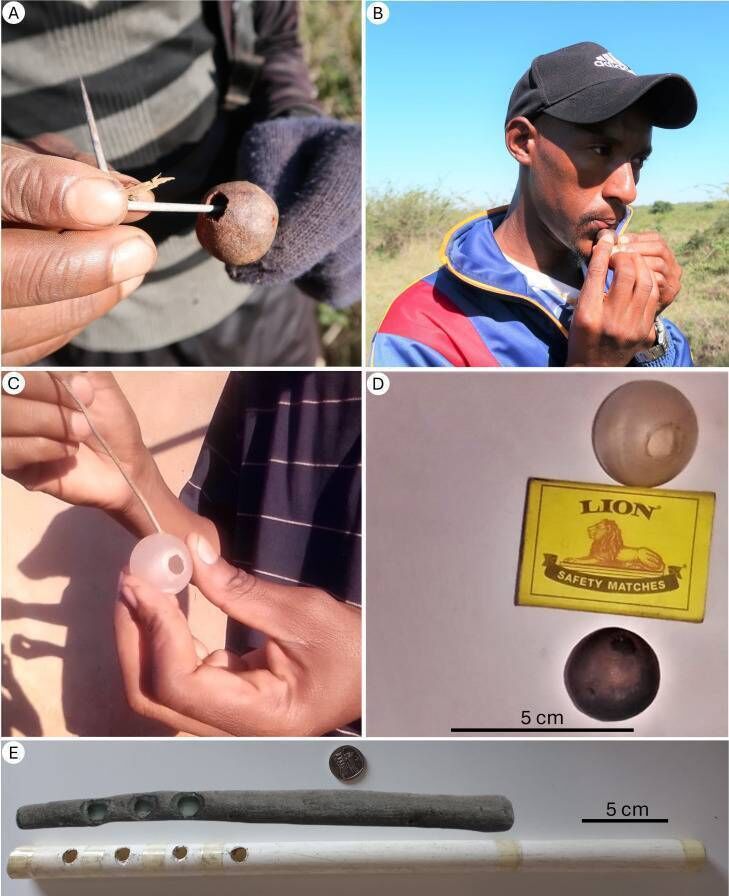

Boy herders, protecting livestock, have learned to interpret and imitate honeyguide calls. To begin a hunt, they summon a honeyguide to help them. The bird, uttering a distinctive call, leads the way to a nest, which may be a kilometre away. The hunters, using a bee-keeper’s trick, light a fire and subdue the bees with smoke.

A tree may have to be felled to remove the honeycombs. A hive will always have some combs not yet filled with honey. Some of these are placed in a prominent location, to pay the bird for its services. Hunters traditionally fear the wrath of the bird — they might have to run the gauntlet of dangerous animals, should they fail to honour their part of the bargain.

But honey-hunting, in an era of flashy cars, trendy fast-food joints, and mobile phones, is said to be declining. When I was visiting Eswatini, then called ‘Swaziland’, 20 years ago, I saw neither honeyguides or ratels. The days of cooperative honey-hunting, back then, seemed to be numbered. But, according to the results of a study just published, the practice continues...

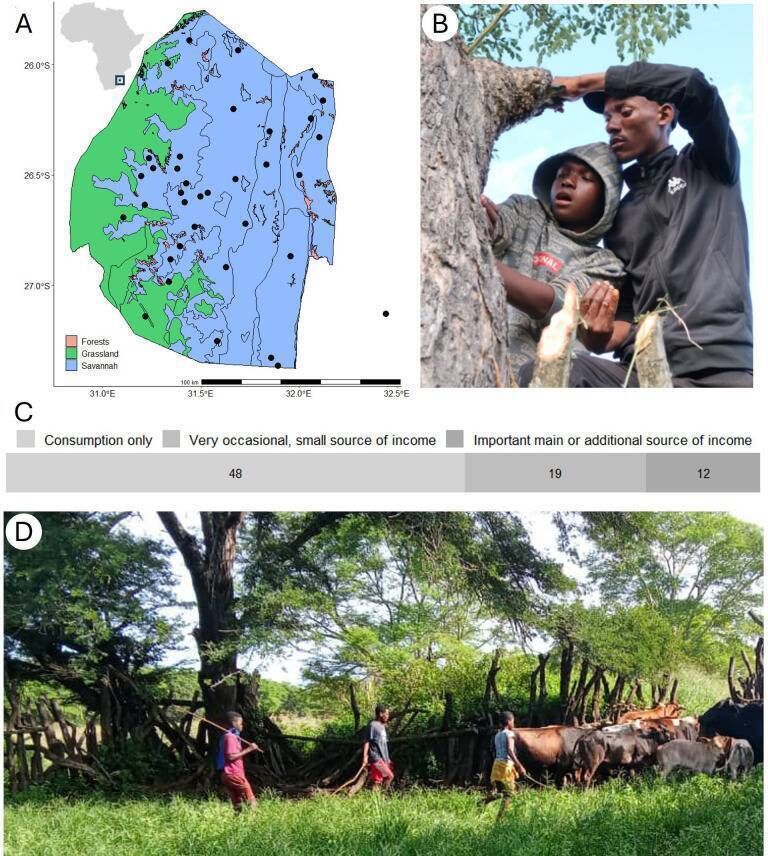

Sanele Nhlabatsi and colleagues from the University of Eswatini interviewed 83 honey-hunters and accompanied some of them in the field. They found that the hunters "use various acoustic signals to communicate with honeyguides, such as an axe striking wood, verbal phrases and whistles".

While it is becoming less common, the scientists found that human-honeyguide cooperation is used mainly as a recreational activity nowadays. Nhlabatsi’s team conclude that, despite increased education and job-opportunities, honey-hunting can survive "without economic incentives for humans, sustained instead by its cultural and social importance".

But spare a thought for the unfortunate bees!

![<p> The International Union for the Conservation of Nature says that “an ecosystem is collapsed when it is virtually certain that its defining biotic [living] or abiotic [non-living] features are lost from all occurrences, and the characteristic native biota are no longer sustained”.</p> <p> The International Union for the Conservation of Nature says that “an ecosystem is collapsed when it is virtually certain that its defining biotic [living] or abiotic [non-living] features are lost from all occurrences, and the characteristic native biota are no longer sustained”.</p>](/cms_media/module_img/9930/4965053_13_augmentedSearch_iStock-1405109268.jpg)