What was the state of nature here 500 years ago?

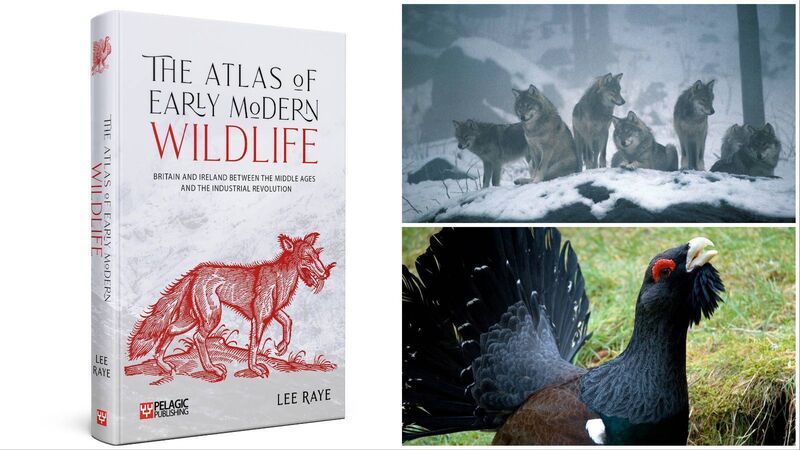

The Atlas of Early Modern Wildlife. Wolves hunted here 250-500 years ago and capercaillie were still found in Irish woodland

What was nature like before the modern period? This is the question my new book, , out this week, aims to answer. By mapping historical records of wildlife, I’ve been able to show just how exciting the nature of the island of Ireland was in the past.

I've found that 250-500 years ago, Wolves and White-Tailed Eagles still hunted widely, and Red Kites as well as Grey Partridges and Corncrakes were still widespread. Black Rats had not yet been replaced by today’s Brown Rats; the Red-legged Partridge was only beginning to be introduced, and Common Cranes roosted in the wetlands alongside Grey Herons.