Islands of Ireland: An island hiding away in the Kerry mountains

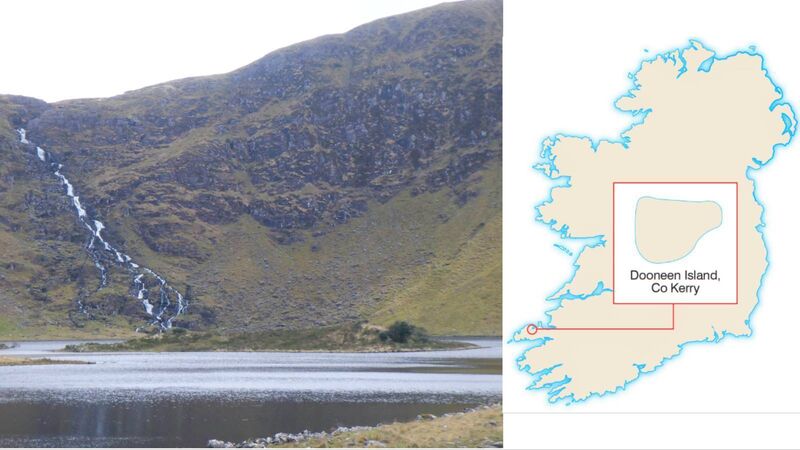

Dooneen Island, Lough Adoon, Dingle Peninsula, County Kerry. Picture: Dan MacCarthy

Islands can be found in the most unexpected places. Having surveyed the coastline zealously for hidden islands it is a joy to discover one hiding away in the mountains. Bullock Island in West Cork lies in an area very hard to reach and is all the more pleasurable to land on for its remoteness. Other islands in the upper reaches of the River Lee were also great to find.

As the road on the northside of the Dingle Peninsula to the Conor Pass begins its ascent there is a magnificent valley away to the south (left). A look at archaeology.ie reveals a map with so many red dots — each representing a monument — as to suggest an outbreak of measles. This is the Ballysitteragh-Beenoskee mountain range and glacial lakes dot the landscape like huge teardrops.