Turning wildlife data into information and insight for decision-makers

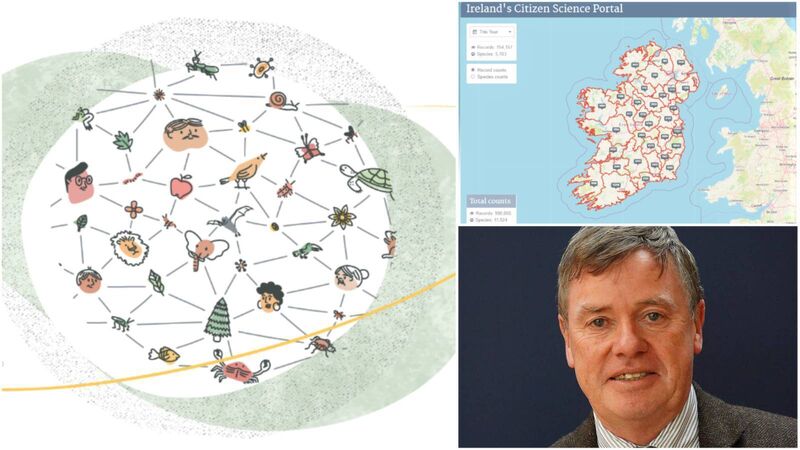

GBIF—the Global Biodiversity Information Facility—is an international network and data infrastructure funded by the world's governments and aimed at providing anyone, anywhere, open access to data about all types of life on Earth. Dr Liam Lysaght, is the new chair of the GBIF governing board

Irish man, Dr Liam Lysaght, has been elected as the new chair of the Global Biodiversity Information Facility. This international network provides open access to data about all types of life on Earth — no small task!

Dr Lysaght is the director of the National Biodiversity Data Centre, collating data about Ireland’s wildlife since its establishment in 2008.

For human populations, we collect census data to get an overview of the dynamics within the population, so that current and future planning for healthcare, housing, schools, hospitals and other essential services can be based on sound evidence. In collating biodiversity data, the motivation is similar. Knowing where certain species and habitats are, their range and population dynamics, and in particular, change in populations over time, all provide the evidence base for developing policies. Data collection is the foundation of what we know about the health of the natural environment that sustains us and everything we know.

Biodiversity data provides insights about which species and habitats are in most urgent need of conservation. It shows us how climate change is impacting species so that we can collectively plan for adaptation. It is the basis for monitoring the spread of invasive alien species. Without good data, there is no way to track change over time.

The National Biodiversity Data Centre collates information from lots of different sources. Some comes in through academics with highly specialised areas of expertise. Historic data comes from museum specimens collected since the Victorian era. Much of the data comes from citizen scientists and volunteers. There are ‘Field Naturalists Clubs’, around since the 1800s, actively collecting biodiversity data, along with a network of county recorders affiliated with the Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland, whose members have been busy since the 1950s cataloguing wild flora and how it has changed over time.

Lots of records come in through the surveys coordinated by Birdwatch Ireland and other conservation and naturalists groups. The Irish Wetland Bird Survey, for example, collates information gathered through an estimated 11,000 volunteer hours each year. These volunteers are skilled individuals. Without them we would not be aware that Ireland has lost around half a million waterbirds, almost 40%, in less than 20 years.

Similarly, without the committed effort of volunteers we would not have scientifically sound or comprehensive information about how butterflies are faring in Ireland. The Irish Butterfly Monitoring Scheme was established by the National Biodiversity Data Centre in 2008. As a result, we now know that overall butterfly populations in Ireland have declined by 35% since 2008.

This is important information. That it is made freely available is core to the work of the National Biodiversity Data Centre and the Global Biodiversity Information Facility. Open access means that researchers can collate data with which to inform policymakers, who then are equipped with the evidence needed to take action.

In taking up his new role, Dr Lysaght spoke of the moral imperative to have good biodiversity data to address the global biodiversity crisis. Information leads to action, at least in principle.

Ideally, when we realise that trends in some species groups are showing alarming declines, collective action is taken in response. Perverse subsidies, for example, that are known to be contributing to downward trends in biodiversity, can be changed so that damaging activities are no longer subsidised. In light of the data showing sudden and alarming decline of butterflies and wetland birds in Ireland, for example, we can develop and implement appropriate responses to halt further declines.

This does happen, although often the response is excruciatingly slow or otherwise insufficient. Sometimes conservation actions are seen as a threat and are actively blocked. It is now well-recognised that politicians and other decision-makers have long ignored and denied data detailing climate change. Now, with ever-strengthening data about the biodiversity crisis, ‘extinction denial’ is taking hold.

In Britain, the government has recently announced plans to revoke hundreds of laws that protect wild places, prevent pollution and maintain standards for water quality. In Ireland, perverse subsidies still persist in the fossil fuel industry, road building, agriculture, fisheries management, and forestry, despite the fact that our understanding of how to mitigate against harm has greatly improved in recent decades.

Recently, there have been calls from high-level decision-makers to reduce the legal protection for endangered birds and other wildlife at EU level, to ease the way for more forestry plantations across Ireland. Unfortunately, the knowledge that Curlew, Lapwing, Hen Harrier and many other bird and invertebrate species have suffered devastating declines as a result of afforestation policies is not filtering through, or worse, the information is simply ignored.

The Living Planet Report released last week reveals a 69% drop in wildlife populations on average in less than a lifetime. The latest ‘State of the World’s Birds’ report released at the end of September, reveals that nearly half of all bird species are in decline globally and that 63% of Ireland’s bird species are declining. Together, this information is most concerning picture yet of devastating collapses in biodiversity. We know that this should be informing policy, yet many decision-makers appear deaf to the data.

In Ireland, conservation organisation BirdWatch Ireland has stated that “zero additional funding for nature conservation in Budget 2023 is shameful". Solid, scientifically sound biodiversity data is crucial. It presents a compelling case for radical improvements in our approaches to conservation. If we are to reverse trends of devastating loss in wildlife that have been accelerating in recent years, we need both good information and the shared understandings of its relevance. Decision-makers will have to strengthen, rather than weaken, the application of conservation laws and policies. Targeted conservation actions must be urgently scaled up. Looking at the bigger picture, getting the decision-makers to listen to the science is now our greatest challenge.

CLIMATE & SUSTAINABILITY HUB