Richard Collins: From Iceland to Ireland for our wild geese

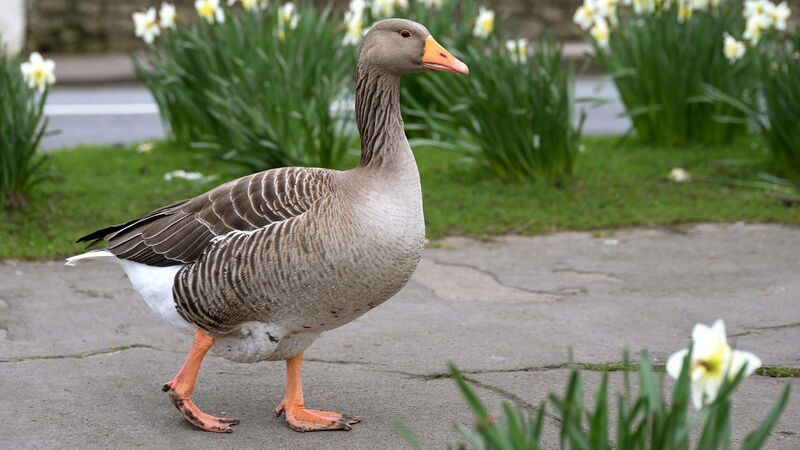

A greylag goose goes for an afternoon stroll by the Lough in Cork. Picture: Denis Minihane

Try from €1.50 / week

SUBSCRIBE“Was it for this the wild geese spread The grey wing upon every tide”

When the Treaty of Limerick was signed in October 1691, the ‘wild geese’ remnants of Patrick Sarsfield’s Jacobite army set sail for mainland Europe, never to return. Yeats’ ‘grey wing’ belonged to a goose which lags behind other geese at migration time — the ‘greylag’.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

You have reached your article limit.

Annual €130 €80

Best value

Monthly €12€6 / month

Introductory offers for new customers. Annual billed once for first year. Renews at €130. Monthly initial discount (first 3 months) billed monthly, then €12 a month. Ts&Cs apply.

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates

Newsletter

Sign up to the best reads of the week from irishexaminer.com selected just for you.

Newsletter

Music, film art, culture, books and more from Munster and beyond.......curated weekly by the Irish Examiner Arts Editor.

© Examiner Echo Group Limited