Knowing your attachment style can help to nurture and strengthen your friendships

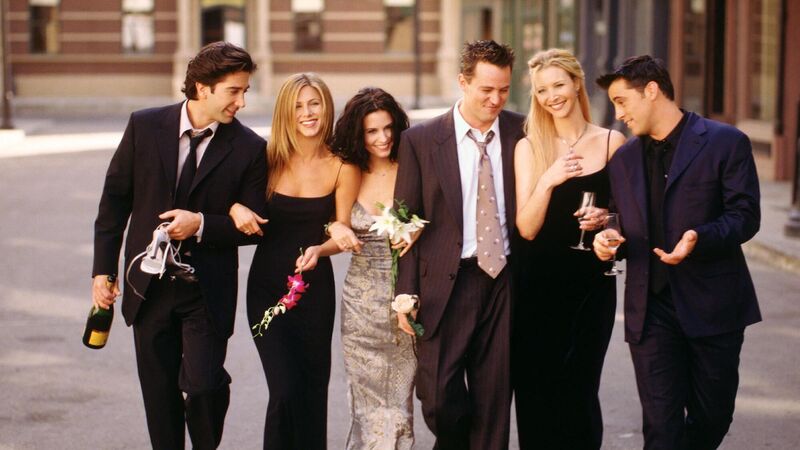

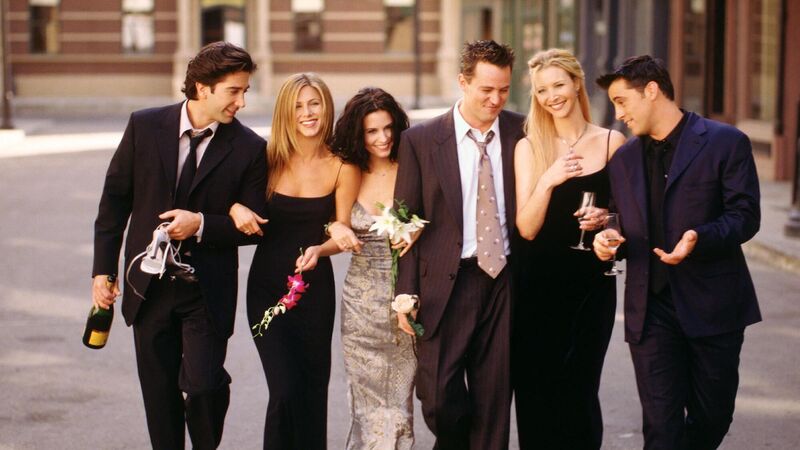

Though the characters in the hit sitcom ‘Friends’ had romantic relationships, their deep friendships endured.

Try from €1.50 / week

SUBSCRIBE

Though the characters in the hit sitcom ‘Friends’ had romantic relationships, their deep friendships endured. Picture: Warner Bros Television

Friends — where would we be without them? Lonely, that’s where. Even having just one or two is crucial for our wellbeing, despite our ingrained cultural belief that romantic love is the only kind that matters. It’s not.

Platonic love — the love of our friends — is, according to Marsilio Ficino, the 15th-century Italian scholar who coined the term, the highest form of love.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

You have reached your article limit.

Annual €130 €80

Best value

Monthly €12€6 / month

Introductory offers for new customers. Annual billed once for first year. Renews at €130. Monthly initial discount (first 3 months) billed monthly, then €12 a month. Ts&Cs apply.

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates

Newsletter

The best food, health, entertainment and lifestyle content from the Irish Examiner, direct to your inbox.

Newsletter

The best food, health, entertainment and lifestyle content from the Irish Examiner, direct to your inbox.

Our team of experts are on hand to offer advice and answer your questions here

© Examiner Echo Group Limited