Book review: False dawns and incremental gains of a writer’s slow recovery through drugs

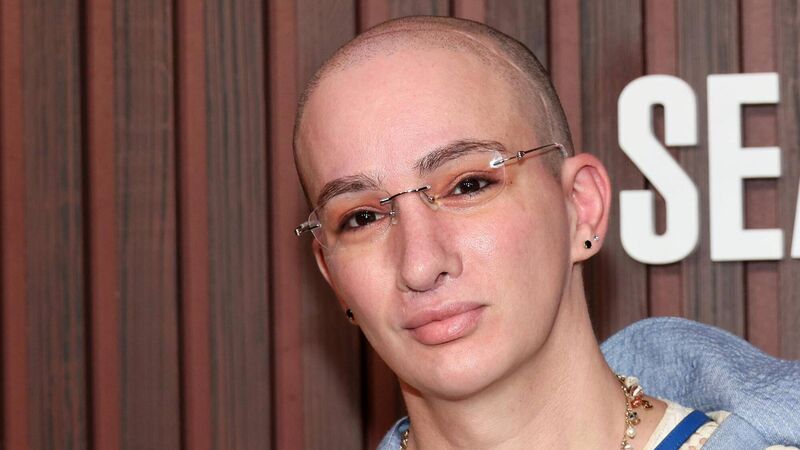

PE Moskowitz: Makes cogent points about America’s vexed relationship with narcotics. Picture: Dia Dipasupil/ Getty

- Breaking Awake: My Search for a New Life Through Drugs

- PE Moskowitz

- Bloomsbury, £9.89

BOOKS & MORE

Check out our Books Hub where you will find the latest news, reviews, features, opinions and analysis on all things books from the Irish Examiner's team of specialist writers, columnists and contributors.