Culture That Made Me: Mel Mercier — Cork is my spiritual home

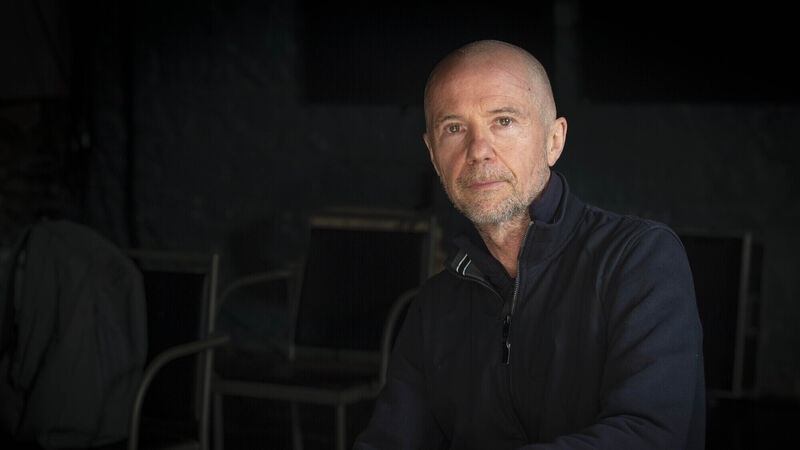

Mel Mercier grew up in Dublin but moved to Cork in 1986 to study music at UCC under his mentor Mícheál Ó Súilleabháin. Picture: Michael Mac Sweeney/Provision.

Mel Mercier grew up in Dublin. In 1986, he moved to Cork — back to the birthplace of his father — to study music at UCC under his mentor Mícheál Ó Súilleabháin.

Over the next quarter of a century UCC and Cork became his musical and spiritual home, and went on to become chair of performing arts at the Irish World Academy of Music and Dance at the University of Limerick.

Mel was nominated for a Tony Award for his soundscore on Broadway in 2012. He’s a contributor to the Cork University Press publication .

Of the LPs my father brought home from his travels with The Chieftains, the eponymously titled 1976 debut album by Kate & Anna McGarrigle is arguably the one that left the most indelible soundmark on our family.

Perhaps it’s the sisters’ mixed French- and Irish-Canadian heritage, coupled with bitter-sweet, heartrending lyrics, melodies and harmonies that gave songs such as 'Heart Like a Wheel' and 'Go Leave' a direct line into our family’s emotional heart.

No other music from those years moves me with the same exquisite force.

One evening in 1979, my mother answered the phone and was greeted by the gentle, dulcet voice of the American avant-garde composer John Cage. He asked to speak to my father.

The following day my father and I packed our bodhráns and bones and took the 46A bus to Donnybrook to meet one of the most influential composers of the 20th century.

Over the following decade we performed 'Roaratorio' with Cage, sean-nós singer Joe Heaney and traditional musicians Paddy Glackin, Liam O’Flynn and Séamus Tansey.

For performances at the Albert Hall, and elsewhere, we didn’t sit in group formation on stage, but were spread out around the auditorium, separated from each other in the balcony, aisles and boxes.

Cage sat at a small table with a lamp, reciting his own reworking of James Joyce’s . We had music stands, but the only thing on them was a stopwatch. Cage directed us to play whatever we felt like playing, intermittently, for a total of 20 minutes within the hour-long piece.

In his uncompromising challenge to traditional music norms, he asked us not to play together or in time with dancer-choreographer Merce Cunningham’s dancers’ jig-like movements. It upended our known musical world and radicalised my understanding of what music could be.

In 1986, I watched Mícheál Ó Súilleabháin on issuing a call to traditional musicians to come to University College Cork to study music. I left Dublin’s leafy suburbs with my drum and bones and moved into a bedsit above a hair salon on Cork’s MacCurtain Street.

When I walked into the music building on the Western Road, I knew I made the right decision. Mícheál was a dynamic and inspirational teacher.

He validated our musical choices. He lifted us up with his eloquent stories of creativity and tradition.

Playing music with him and fellow students in the Ó Riada Room, or Sulán Studios in Ballyvourney, or the heaving sessions in the Rockview Bar on Gillabbey Street was joyful, sometimes experimental and frequently wild.

Many of the most memorable concerts I’ve played in or attended were at small and intimate Cork venues in the ’80s and ’90s, amongst them the Lobby Bar, UCC’s Aula Maxima and the Triskel Arts Centre.

I loved playing at the old Triskel — a windowless, narrow 100-seater auditorium — with Mícheál Ó Súilleabháin, especially on occasions when we did two shows in one evening, because in the middle of the fleeting bliss of playing 'Oíche Nollaig' in the first concert I’d realise we’d get to do it all again later, for a lively, late-night audience.

I first heard the wonderful bodhrán player John Joe Kelly at the Triskel. There was electricity in the air that night. John Joe played with Ed Boyd on guitar and Mike McGoldrick on flute.

I remember being stunned by John Joe’s exceptional technical ability and musicality, and the exuberance and audacity of the rhythmic grooves he created with Ed Boyd. At the interval, in sonic shock, I couldn’t get out of my seat.

For years afterwards at parties with friends in Cork, late-night revels climaxed when we gave ourselves up to Flook’s album and were taken to the next level by the power pulse of John Joe’s master drumming.

The year I moved to Cork, my brother Paul introduced me to the magic of live theatre with his emotionally charged, highly inventive, physical tour-de-force production of Studs at Dublin’s SFX theatre.

Two years earlier, with the production of his rock musical , his pioneering company, Passion Machine, launched a form of innovative, inclusive theatre that created a new audience for contemporary Irish plays, including his own and , and early plays by other Irish writers, including Roddy Doyle.

When I began to make music for theatre on a regular basis in the 2000s, I was still spellbound and intoxicated by Paul’s work, as I am today.

My own work in theatre kicked off in earnest in 2000 when I met with the British theatre director Deborah Warner for the first time at Cork’s Imperial Hotel.

Over a cup of tea, Deborah told me about her plans to direct a production of Euripides’s at The Abbey Theatre with Fiona Shaw in the title role.

That meeting led to my first job at the Abbey and my first of many collaborations with Deborah and the peerless Fiona Shaw.

The following year, Pat Kiernan, Corcadorca Theatre Company’s brilliant and ground-breaking artistic director, invited me to join his ambitious and spectacular promenade production of in Fitzgerald Park. I loved working with Pat. I discovered I also loved making sound designs for theatre in the open air. Over the following 20 years, I found myself making music with Corcadorca in unlikely settings... from Haulbowline naval base, the old Ford factory, to Cork’s city streets for .

The Corcadorca experience I treasure most is the 2017 Spike Island production of Carol Churchill’s .

Taking the boat from Cobh to the island every morning for a month with Pat and the actors and returning late at night on the high-speed RIBs after a day of pure play was exhilarating.

Every rehearsal felt like an adventure. When the play opened, Corcadorca’s audience made the pilgrimage to the island in droves.

Every evening, as the anti-war, dystopian drama unfolded, daylight slowly faded, giving way to illuminating electrical lamps framing theatre’s magic in the darkness of an island night.

Sebastian Barry’s 2016 novel, , is a gripping and atmospheric frontier saga set during the bloody period of the American Indian Wars and the American Civil War.

Gender and identity are core themes. It’s narrated by Thomas McNulty, a 13-year-old boy who emigrated from Sligo in 1851 after his family died in the Great Famine.

While fighting as a mercenary soldier during the civil war, McNulty falls in love with John Cole.

The tenderness of their love is beautifully portrayed. Barry’s rapturous evocation of the magical and transgressive power of performance is a marvel.