Author interview: A moment when the world tips over into something else

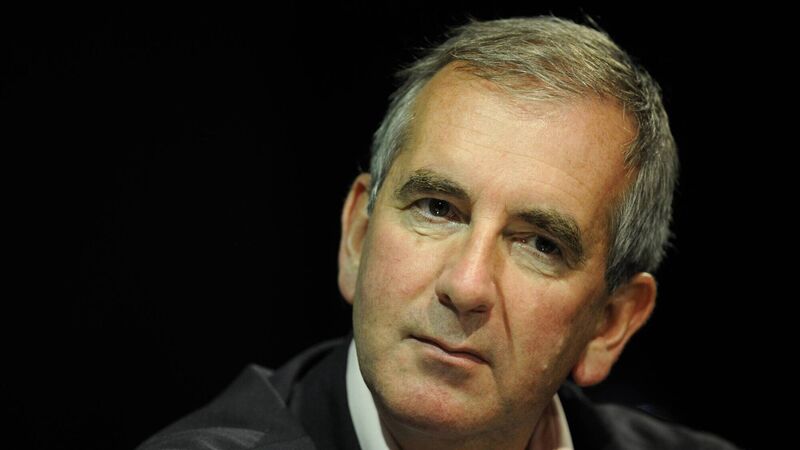

Robert Harris: They had promised Home Rule and they simply had to deliver it. And equally the Tory party under Bonar Law and with Carson was adamant that they would not allow a fully united Ireland. Picture: Getty Images

- Precipice

- Robert Harris

- Hutchinson Heinemann, €16.99