Book review: Clifford is unflinching in his takedown of Garda procedure

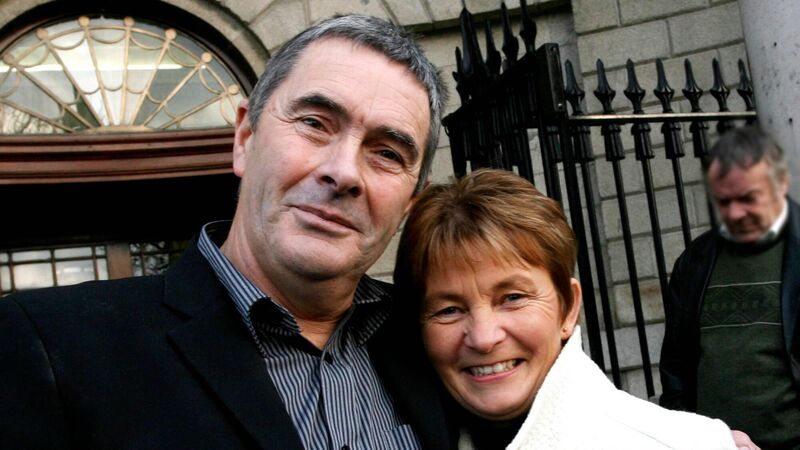

A happy Martin Conmey of Porterstown Lane, Co Meath, with his wife, Ann, in November 2010, after his conviction for the manslaughter of Una Lynskey in 1972 was quashed by the Court of Criminal Appeal. File picture: CourtPix.

- Who Killed Una Lynskey? A True Story of Murder, Vigilante Justice and the Garda ‘Heavy Gang’

- Mick Clifford

- Sandycove, €19.99

For his latest book, Mick Clifford, the award-winning journalist from this parish, takes us back to the Ireland of 1971 and the October killing in Meath of a 19-year-old civil servant, Una Lynskey, and the terrible consequences which derived from that foul deed.

BOOKS & MORE

Check out our Books Hub where you will find the latest news, reviews, features, opinions and analysis on all things books from the Irish Examiner's team of specialist writers, columnists and contributors.