Laethanta Saoire: One Faithful Summer, by Billy O'Callaghan

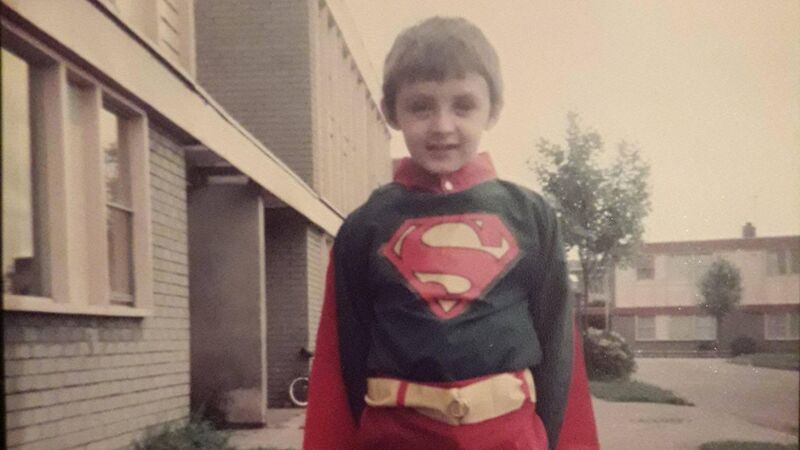

Cork author Billy O'Callaghan as a child.

In memory, childhood summers seem forever golden, those long days spent kicking a ball around hard-baked fields, peeling away sheets of skin from our sunburnt shoulders, splashing in streams for thorneens and tadpoles, breathing air ripe with the tang of cut grass and bonfires. Sweltering months defined by World Cups, best friends, Choc Ices and Fat Frogs, the screaming coldness of the seaside waves with none of us able to swim. When I think back now, this is a lot of what comes to mind. Until I begin to sift.

Because it wasn't all sunshine. Maybe I'm remembering wrong but I recall the summer of 1985 in particular as nothing but rain. And it fit a mood, a year of devastating famine and football stadium disasters, even if a lot of the actual detail passed over me. Because at ten years old I still kept my horizons close. I'd been to Dublin once, on the train, and a couple of times to Kerry, but everywhere else amounted to little more than names on a map, and worlds removed. The tragedies that filled the news caused a sick feeling in the pit of my stomach, but until the Air India plane crashed on our county's doorstep, life, at least to my mind, had kept its grimness at relatively distant bay.