Karl Whitney: Independent message fades within art’s stifling corporate structures

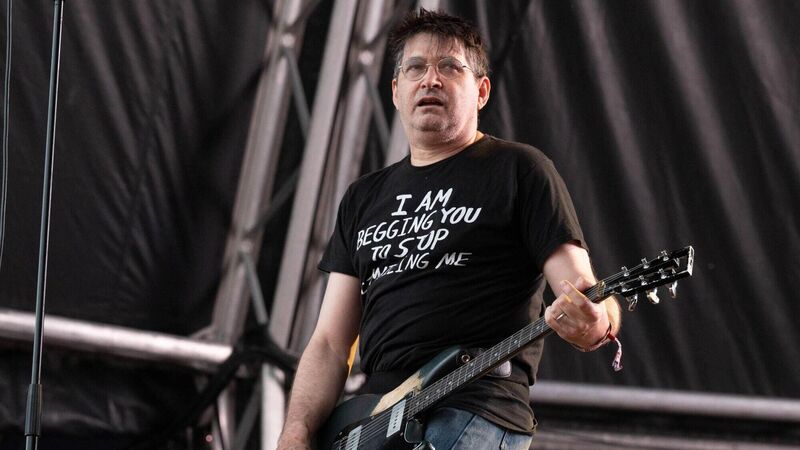

Steve Albini was fiercely independent and a severe critic of the music industry and its exploitation of young bands. Picture: Jim Bennett/WireImage

The notion of independence has been on my mind lately. Mainly because the rigorously independent producer and musician Steve Albini died, leaving behind him a legacy of quite astounding records, including Pixies’ , PJ Harvey’s and Nirvana’s .

What was notable about him, beyond the exacting quality of his work and his habitual acidity (and occasional obnoxiousness, at least earlier in his career), was the unpretentious and critical approach he adopted towards his own industry.

BOOKS & MORE

Check out our Books Hub where you will find the latest news, reviews, features, opinions and analysis on all things books from the Irish Examiner's team of specialist writers, columnists and contributors.