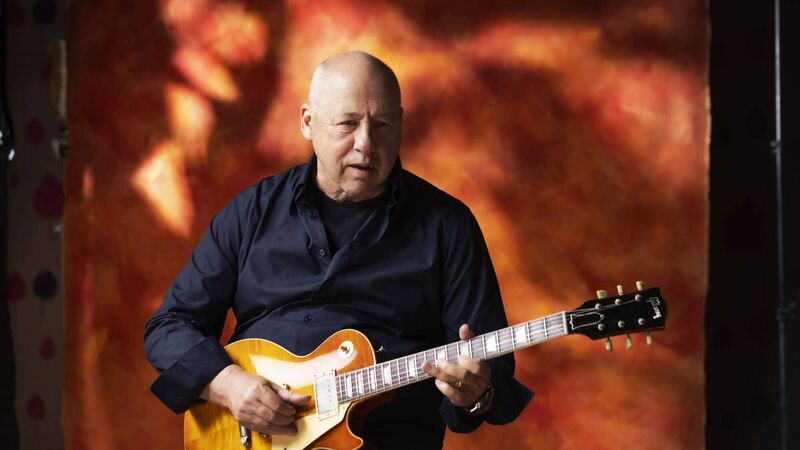

Dire Straits' Mark Knopfler: Swinging from a cub journalist to a rock legend

Mark Knopfler: Legendary singles were inspired by real-life interactions, informed by a background in journalism. Pics: Murdo MacLeod

How do you introduce Mark Knopfler?

Helped launch the music television era; helped launch — with Brothers in Arms — the CD era; was in a band — Dire Straits — that spent over 1,100 weeks on the UK album charts?