Book Review: The Kidnapping recalls the survival of Don Tidey after IRA abduction

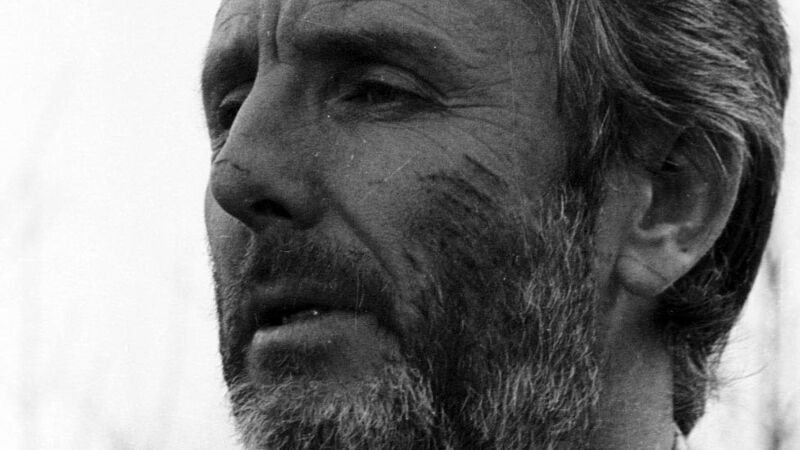

Businessman and kidnap victim Don Tidey after being rescued in December 1983; he had been held captive by a ruthless IRA gang for 23 days in rural woodland in Co Leitrim. Picture: Eamonn Farrell/RollingNews.ie

- The Kidnapping: A hostage, a desperate manhunt and a bloody rescue that shocked Ireland

- Tommy Conlon and Ronan McGreevy

- Sandycove, €16.99