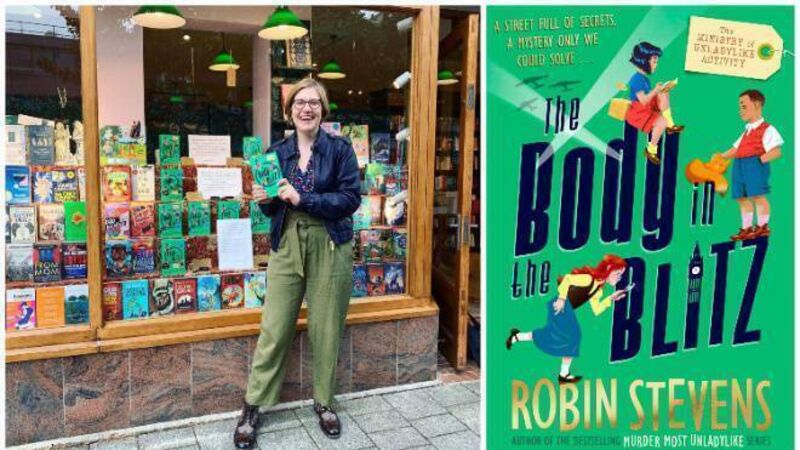

Author Robin Stevens on her autism diagnosis: 'Stories are what help me make sense of the world'

Robin Stevens: "I definitely think that writing, for me, is how I understand myself and the world — and it all makes much more sense now."

“The thing I would always say, when asked why I love writing, is that 'stories are what help me make sense of the world'. I think it's a very interesting phrase that I look back on, and think about now, because I think it's even more true than I really understood, even from a very young age.”

Robin Stevens’ enthusiasm shines through the screen as the writer says hello over Zoom — sat in a home office, with a jam-packed bookcase occupying almost the entire wall in the far distance, her energy is of someone who’s living among her interests and her passions.