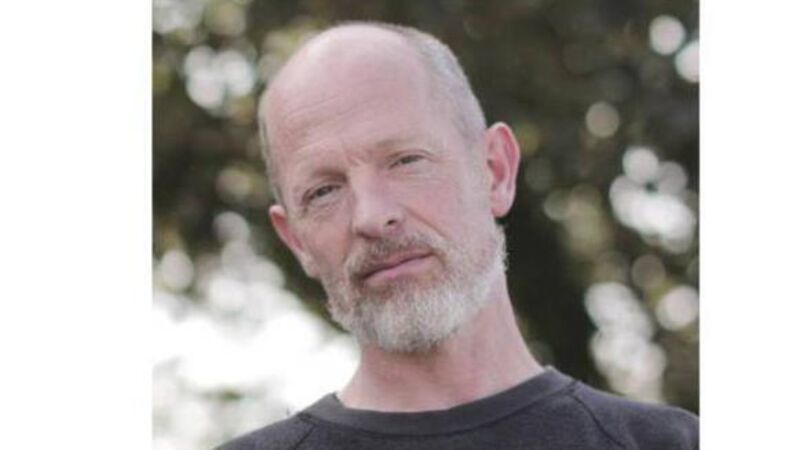

Culture That Made Me: Michael Keegan-Dolan on dance heroes and great music

Michael Keegan-Dolan brings his acclaimed MÁM show to the BGE Theatre in Dublin.

Michael Keegan-Dolan, 54, grew up in Clontarf, Dublin. He trained at London’s Central School of Ballet. In 1997, he founded Fabulous Beast Dance Theatre, which created several Olivier Award-nominated productions, including Giselle, and The Rite of Spring.

His new company Teaċ Daṁsa’s production of Swan Lake/Loch na hEala was widely acclaimed, and the Kerry-based ensemble’s subsequent show, MÁM, will be performed at Bord Gáis Energy Theatre in Dublin on July 13 and 14. See: www.bordgaisenergytheatre.ie.