Ireland In 50 Albums, No 6: Astral Weeks, by Van Morrison

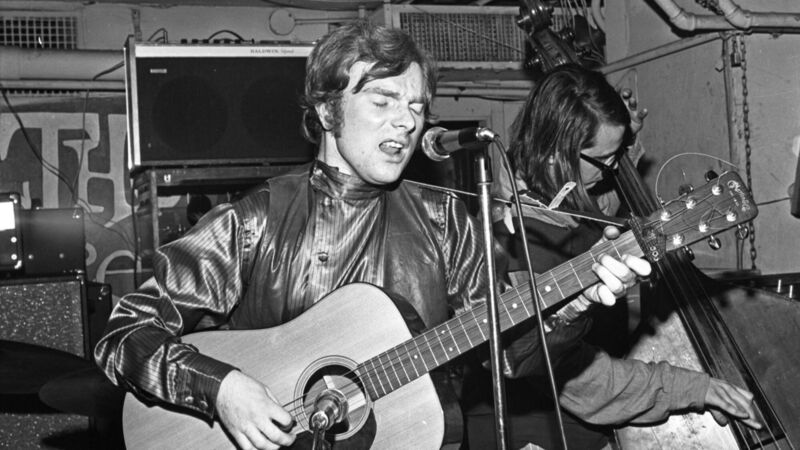

Van Morrison performs at a Warner Brothers party at Steve Paul's The Scene nightclub in 1969 in New York. (Picture Popsie Randolph/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty)

Van Morrison fell in love while on tour of the United States with his band Them in 1966. Janet Rigsbee was in the audience at a gig in San Francisco. When the pair locked eyes, it was “alchemical whammo”, according to the 19-year-old model.

Morrison began calling her Janet Planet. He returned to Northern Ireland, moving back in with his parents, but they pined for each other. Morrison told her that if she heard him on the radio it meant he was on his way to find her.