Book Extract: Multiple Joyce: 100 Short Essays about James Joyce's Cultural Legacy

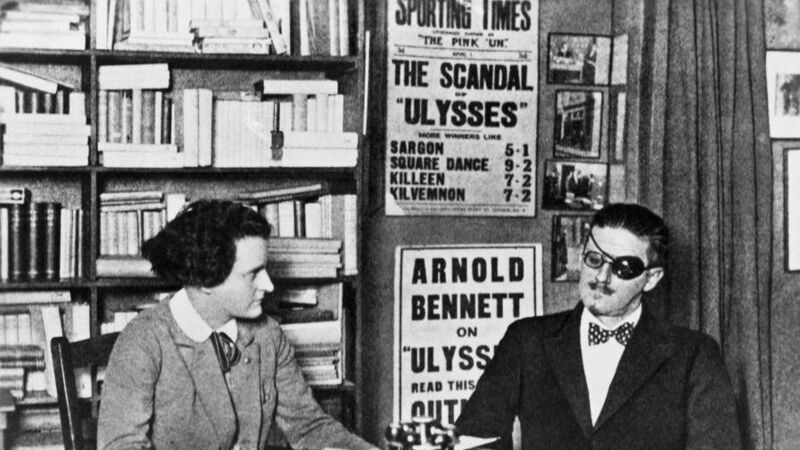

Joyce and his publisher Sylvia Beach sitting together in her office at Shakespeare and Company (12, rue de l’Odéon, Paris)

Here’s a well-known photograph of Joyce and his publisher Sylvia Beach sitting together in her office at Shakespeare and Company (12, rue de l’Odéon, Paris) and, behind them, two newspaper placards, no doubt obtained locally, and perhaps surreptitiously.