How Ulysses by James Joyce signalled a change in the history of literature 100 years ago

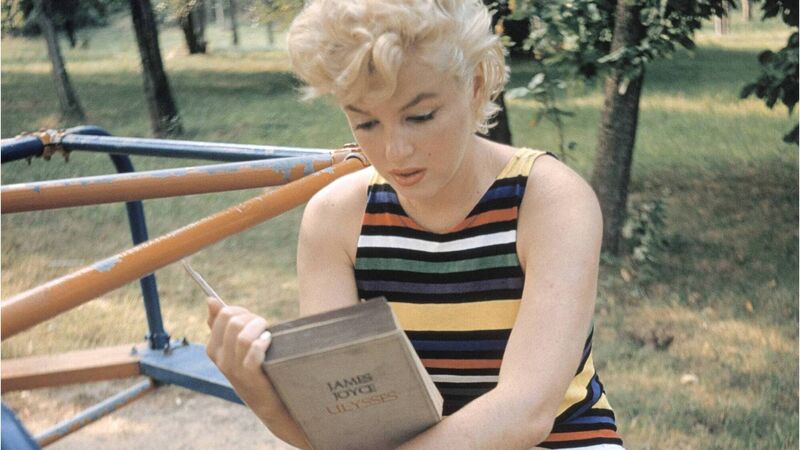

Ulysses is not a beach read, despite a photograph of Marilyn Monroe reading it in swimwear. Picture: Eve Arnold/Magnum Pictures

A member of the Royal Irish Constabulary was killed in Killarney by the IRA on February 2, 1922, a month after the passing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in the Dáil and the establishment of a provisional government to oversee the handover from British rule. It can be seen as marking the beginning of a new wave of violence that would become Ireland’s Civil War.

Earlier in the morning of that same day, a woman named Sylvia Beach stood in the Gare de Lyon in Paris waiting for the arrival of the express train from Dijon. She was not looking for a passenger, but rather the train’s conductor and a package he had been entrusted to carry. It contained two advance copies of James Joyce’s Ulysses, a book for which Sylvia Beach had to borrow and beg the money to pay the printer. It reached her hands just in time for the agreed deadline — the author’s 40th birthday.