Alice Taylor: 'If we wrong nature, we’ll pay a terrible price'

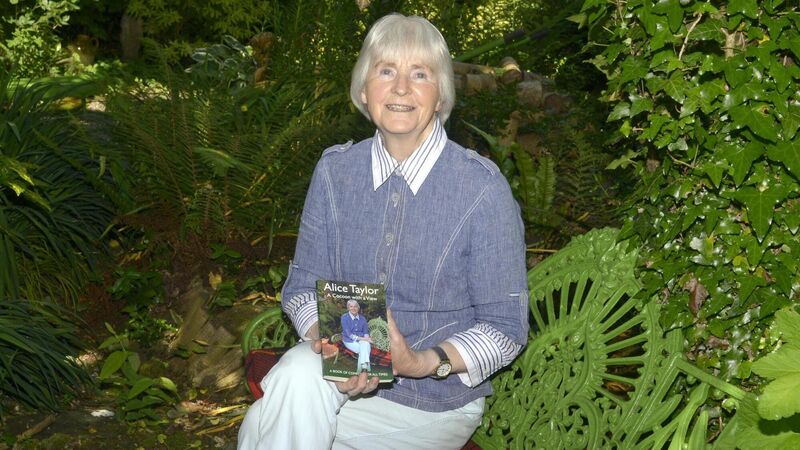

Alice Taylor. Picture: Denis Boyle

Alice Taylor, 83, grew up on a farm in Lisdangan, Newmarket, along the Cork-Kerry border. In 1961, she moved to Innishannon, Co Cork, when she married. In 1988, she published To School Through the Fields, the first of several best-selling memoirs about life and customs in rural Ireland. Her latest book, Tea for One, is published by O’Brien Press.