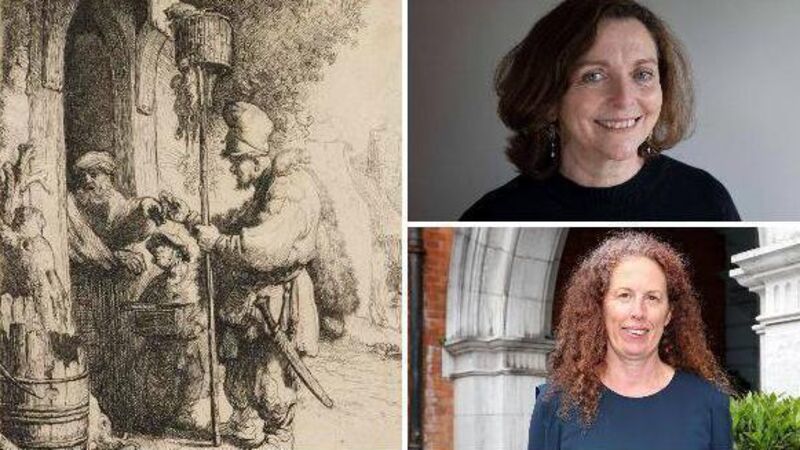

Rembrandt in Cork: 'This is the last outing the prints will have in our lifetimes'

Rembrandt in Print, at the Crawford Art Gallery in Cork. All Rembrandt images courtesy of Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Rembrandt in Print, at the Crawford Art Gallery in Cork, has been one of the most successful arts events in Ireland this year. The exhibition comprises 50 hauntingly beautiful etchings and drypoint prints by the 17th century Dutch master, Rembrandt van Rijn, on loan from the Ashmolean Museum at the University of Oxford. They describe religious and domestic scenes, and feature landscapes and portraits, including — most poignantly, perhaps — those of the artist himself and his wife, Saskia.