Book Review: An overview of Fine Gael's relationship with the status quo

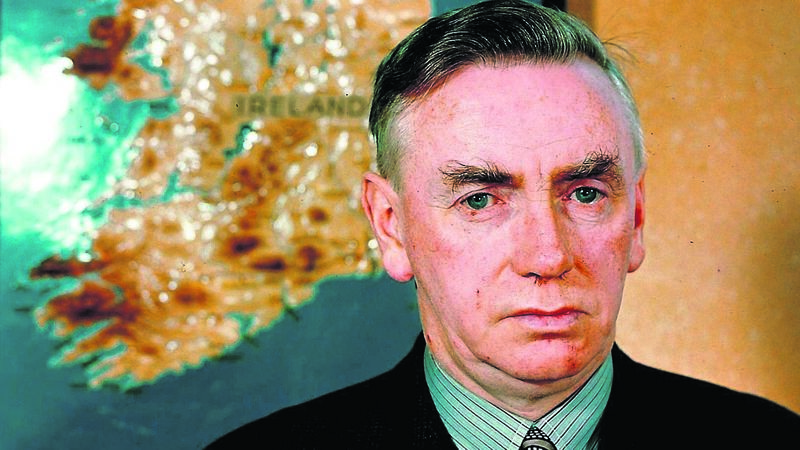

John A. Costello, former Taoiseach: 'A poodle of the Catholic hierarchy.'

- Saving the State: Fine Gael from Collins to Varadkar

- Stephen Collins and Ciara Meehan

- Gill Books, €24.99