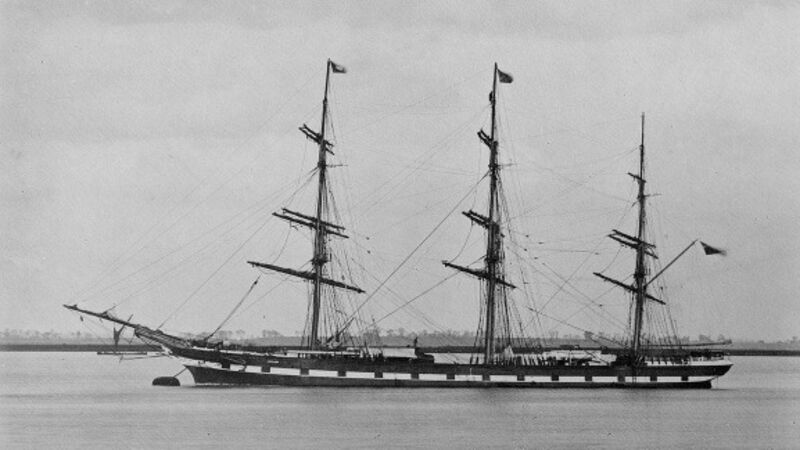

Only two survived, one a hero: A look back at the sinking of the Loch Ard 140 years ago

An 18-year-old Dublin woman was one of only two survivors from the wreck of the Loch Ard when it sank off the coast of Australia 140 years ago this month, reports The other, a boy from Tipperary, saved her life.