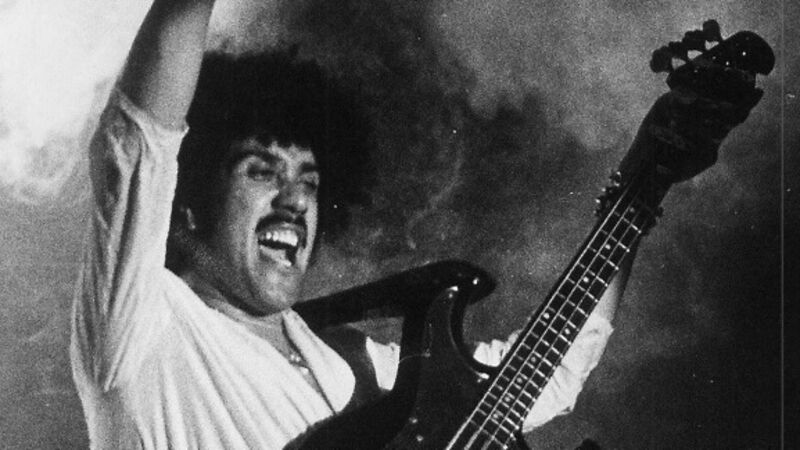

Phil Lynnot's biography highlights how proud the rocker was to be Irish

PHIL LYNOTT was the original Irish rock star. Wiry, exotic, and always fabulously turned out, in late 1960s Dublin he looked like a visitor from another planet. Yet he was fiercely proud of his Dublin identity, with a knowledge and appreciation of Irish culture and heritage that put peers to shame.

Such were the contradictions that drew rock biographer Graeme Thomson to Lynott. In his new biography of the Thin Lizzy singer — written with the approval and co-operation of the musician’s estate — Thomson chronicles Lynott’s ascent from working class Crumlin to the top tier of global rock, and explores the degree to which his background as the son of a Irish mother and British Guyanan father moulded his identity.