Louise O'Neill: Jesy Nelson, 'blackfishing' accusations, apologies, and cancel culture

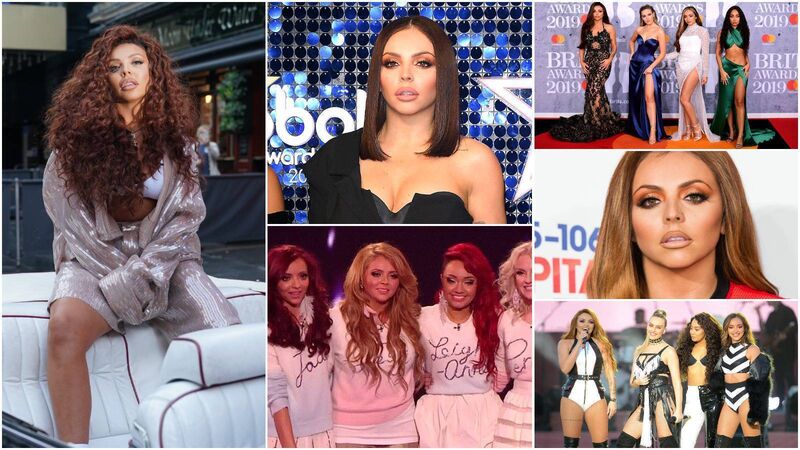

Jesy Nelson of Little Mix

Jesy Nelson, a former member of the girl band, Little Mix, released her debut solo single last week. Both the lyrics of the song, in which she described loving ‘bad boys’ who are "so hood, so good”, and the video itself have been criticised; Nelson has been accused of ‘blackfishing’, altering her physical appearance with lip fillers, excessive tanning, and wearing traditionally Black hairstyles to look more racially ambiguous. (Nelson has denied these accusations, saying she’s “very aware” she’s a white woman)