Before ‘Saving Private Ryan’ there was ’Saving Private Smith’

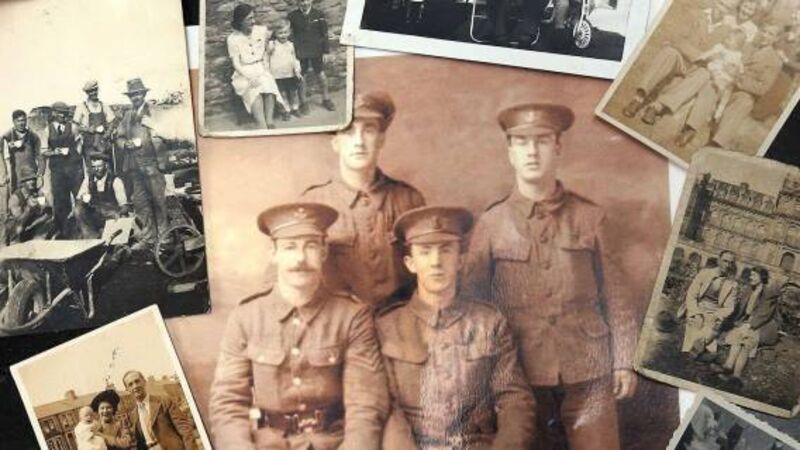

There’s a story behind the name that isn’t there, a sixth brother, Wilfred, and a century after the First World War, an historian has dug out the archives.

Wilfred Smith’s survival is a story of sacrifice amid a war that demanded so much of it from virtually every family in Britain.