Donal Canniffe: ‘A huge win and a huge loss. I can’t separate them’

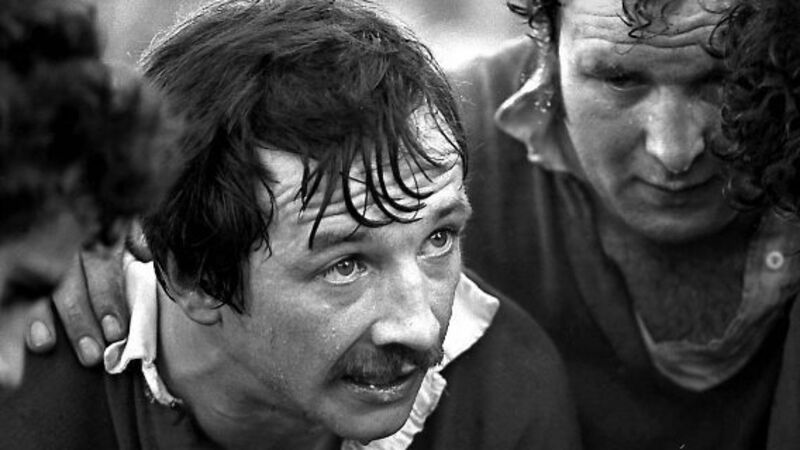

Donal Canniffe, half time, Thomond Park, October 31, 1978

It no longer stands alone. And neither does he. For 38 years, Donal Canniffe held the distinction of being the only Irishman to captain a senior team to beat the All Blacks. It was he who led them out that day, a day that’s been immortalised in song, books, documentaries and even a brilliant stage play; a day, that even if there had been no songs, books or even victory, he could never have forgotten anyway.