Gravity no barrier in speed climbing - the Olympics' quickest sport

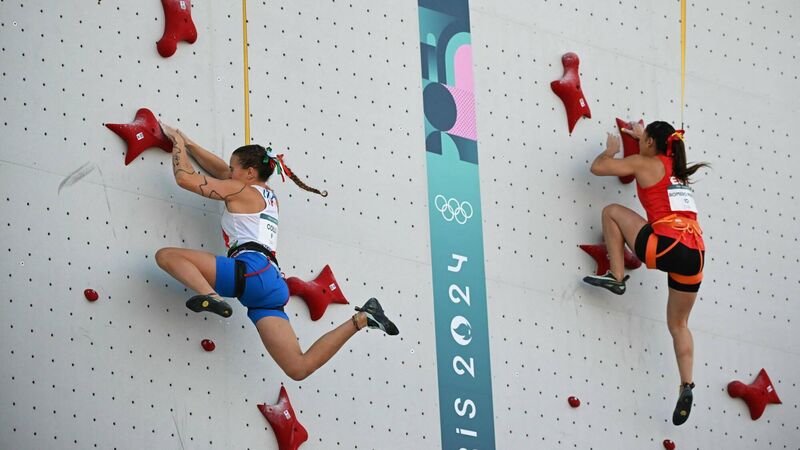

Italy's Beatrice Colli, left, competes against Spain's Leslie Adriana Romero Perez in the women's sport climbing speed preliminary round heats

It would be a surprise if even a handful of the Irish hordes that helped fill the Velodrome in Marseille for the opening game of the Six Nations last February stumbled across the Arkose Prado hidden away down an innocuous laneway and no more than the kick of a ball from the stadium.

The Arkose Prado is a restaurant (and it sells cracking burgers and fries with a beer for a very reasonable price) but it’s also a rock-climbing centre. This might seem like a strange hybrid of a business, but it is very French and it speaks for how embedded a sport virtually unknown in Ireland can be elsewhere.