Armagh and Donegal have held a mirror to each other

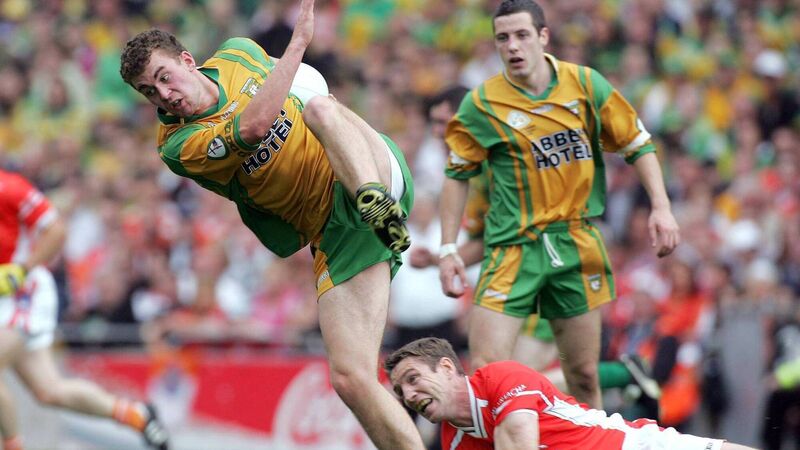

Ulster Senior Football Championship Final 9/7/2006 Donegal vs Armagh Eamon McGee of Donegal gets tackled by Kieran McGeeney of Armagh Mandatory Credit ©INPHO/Lorraine O'Sullivan

Minutes before Donegal took to the field to win their first Ulster title under him and the county’s first in 19 years, Jim McGuinness produced five sheets of paper, each a blown-up photograph from other Ulster final days.

The common denominator was that Donegal had played in each of those finals and on every occasion it wasn’t a Donegal captain that had taken home the cup. Instead it had been a couple of Derry men – Henry Downey in ’93, Kieran McKeever in ’98 – and one particular Armagh man in 2002, 2004 and again in 2006.