Clash of the Ash: The bookie, the hurley and the wider war

It came as a bolt from the blue and ended up shaking the ground beneath their feet. 20 years ago, Tommy Dunne was a 29-year-old All-Ireland winner, former Hurler of the Year and three-time All Star. With a hurley he was spellbinding. It was only a matter of time until someone tried to take advantage of that.

The idea was the brainchild of Eamon McLoughlin. Now the CEO of Fortitude Sports Management, he was reading a newspaper and noted a picture of a player brandishing his hurley. It commanded the entire front page. Their scrawled name was clearly visible above the bas. GAA was part of his upbringing, having represented Dublin at minor level while his brother Mark was once chairman of Warwickshire GAA. Suddenly he saw a chance to bring together his two worlds.

They would source eight elite players involved in the 2003 All-Ireland semi-finals and agree a deal to use hurleys bearing his client’s logo, Paddy Power. From that seed grew an obstreperous plant that spread across several of the national game’s plots. It almost felled commercial agreements. There was a standoff between an association threatening suspension and players warning of strike action. It would become an essential battle in the association embattled defence of amateurism.

Dunne first pucked around with that hurley in Thurles, heedless to how it would become a weapon at the centre of all-out war.

“For us, it was a fairly hefty sum of money,” the Tipperary legend recalls. “It was only for the semi-final. There was no talk of anything like it earlier in the championship. We were playing Kilkenny. I was really taken aback at the amount.

“I remember going along with it even though initially I didn’t think it would happen. It would’ve been the first time it ever happened for a sponsor to be on a hurley. In my mind I kind of thought it wasn’t going to wash.

“We were training less than a week before and I had it on my hurley at this stage. The one thing putting me off was how it looked. I didn’t want it on my hurley, it bothered me. I just didn’t like it. It was alien.

“I had it on the hurley training away and no one said anything. One evening we were coming out of the tunnel under the stand on the way to the pitch and the county chairman called myself and Brendan (Cummins) over.

“We got it then. I can’t remember the exact conversation, but it was made clear to us no in no uncertain terms that they did not agree and did not want us to do it. I walked away thinking, ‘this is a bigger deal than I realised.’”

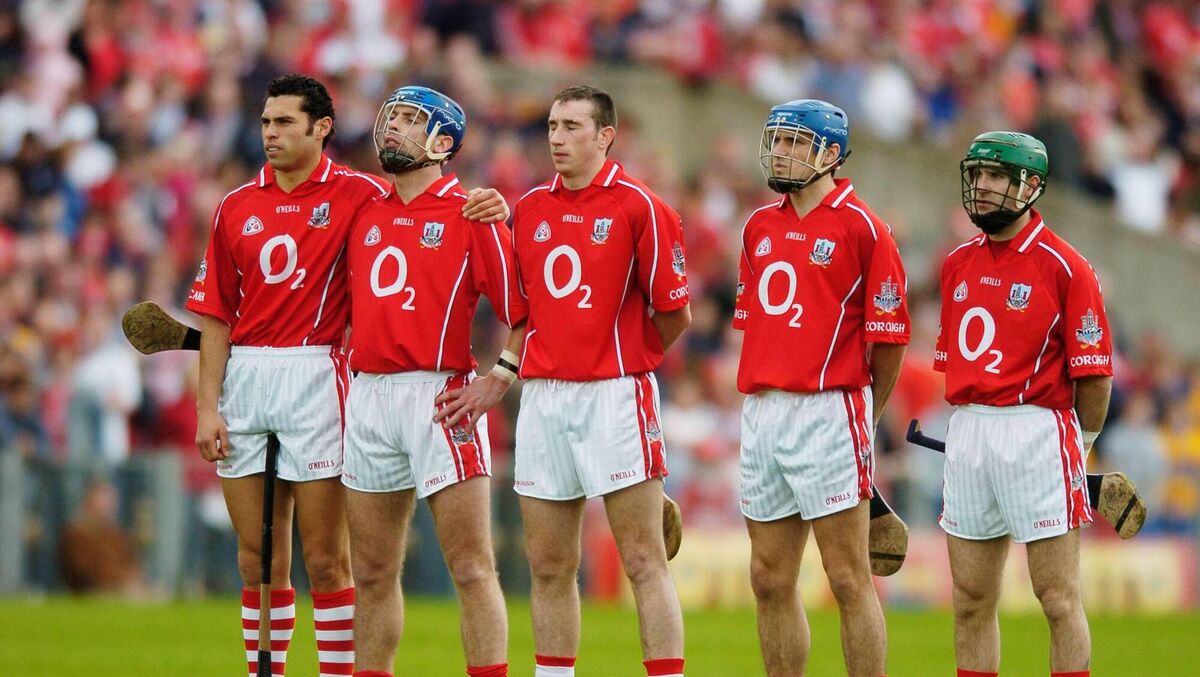

Players from all four counties signed up. As well as Dunne and Cummins, Kilkenny pair Eddie Brennan and Martin Comerford were on board. In the first semi-final, Cork drew with Wexford. That day Paul Codd, Damien Fitzhenry and Cork's Seán Óg Ó hAilpín all played with the branded stick. They were to be paid €750 per game. That guerrilla marketing sent sparks flying all over HQ. Rather than refuse the bait, the association reached for gasoline and poured generously.

In his book Ó hAilpín remembers the call coming from the PR firm. It finished a draw, Cork 2-20 Wexford 3-17. His younger brother had been part of the agreement but pulled out before throw-in.

“We were offered a few bob and we said yes – if you got a few quid without harming anyone, what was the problem? It was gas: a courier called to the house and brought away the hurleys, and a couple of days later they came back stamped with the logo.

“In the end I played with the logo but Setanta didn’t because we felt he was too young to be getting that kind of focus. Because Setanta wasn’t going to play with a logo on his hurley, he had to use a different stick from the one he’d been training with. Maybe that’s why he kicked his goal.”

As soon as the final whistle sounded, shots rained from all sides. GAA president Sean Kelly warned that Paddy Power could be evicted from its corporate box in Croke Park. The Games Administration Committee were reported to be considering 24-week bans for the players in question due to a breach of rule 14 in the GAA’s official guide regarding playing gear. GPA chief executive Dessie Farrell blamed the broker for taking advantage of amateur players. McLoughlin returned fire by suggesting they should be trying to secure their own deals.

As for the players themselves, Wexford captain Paul Codd lashed out at GAA chiefs and called on the participating teams to boycott the following weekend’s fixtures if they were punished. He put his money into the players’ fund. This fight wasn’t about that. The tremors rattled the board. Just as McLoughlin forecast.

“I knew there would be a big reaction. At that time, it was so anti-commercialisation of players. Once the players were brave enough to stand up and say this isn’t about us. This is for players in general.” As GAA president at the time, Sean Kelly stresses now it was never about the individuals. His wrath was aimed predominately at the bookmakers.

“This is what they do, these witty stunts,” he explains. “It was ambush marketing. As an organisation, we couldn’t condone that. When I reacted so strong vocally, they pulled back.” Before the replay, the bookie confirmed they were suspending the scheme while still honouring agreed payments. Kelly chuckles when reminded of how their spokesperson framed it. Talk of how an “over the top reaction” forced them into cancellation yet still generating publicity with promises of continuing payments.

“They had their publicity. He had his kick. ‘We’ve gone far enough and now…’ He could spin it to say it was because of the GAA and he was still for the players. They’d go back to their cupboard and come up with something else. I’d say they were secretly delighted with me.” In reality, there were commercial interests on both sides. Gradually the GAA would move towards banning gambling and alcohol sponsorship. At the time a headline alcohol sponsor were on board and their satisfaction was a priority.

“Importantly, at that time Guinness were sponsoring the hurling championship. It was a cheap one to get all that publicity taken away from our sponsors. They were really good sponsors, in many respects they helped create the popularity of hurling with their campaigns and billboards.

“Looking back, that day was the start of vocal commercialism. Utilising the selling power of the game and the players. In that sense we probably took it more seriously than we should have. There was an element of progressiveness about it. If you have a commodity, you can use it to your advantage especially if it helps the game and the players who are providing us with all this entertainment.”

Consider the context. GAA players might do the odd small campaign, but their name was effectively worthless as a commodity. There had been a series of TV adverts straining for an appeal in rural Ireland. Cork’s John Fenton partnered with farming company Cepravin. Tony Doran promoted Leo Yellow products for dry cow and calf scour.

Out west, Joe Cooney was with Broad Spec fluke and worm drench for sheep and cattle. There had been conflict between the Kerry football team and the GAA over sponsorship deals in the 1980s and it all formed part of a slow erosion. The commercial value of players was starting to become apparent. Change was coming.

By 1999, the Gaelic Players Association was formed and a year later campaigning began to improve the conditions for county players. At the same time, some big names were providing coaching clinics or presenting medals. McLoughlin had orchestrated the Puma deal a few years previous. The net profit was still a pittance.

2003 was the time to stick or twist. Had the GAA pushed forward with the swing of a hammer, the fallout would have been severe. Players dug in and were united. There was never any question of it being an issue in the dressing room.

“I never once got that sense,” says Dunne. “I actually do remember another commercial opportunity came up and I couldn’t do it. Anyway, I recommended another player on our squad. Your man went off did it and he came to a week later to say, ‘Jeez, that was a really nice touch. Why didn’t you keep it for yourself?’ That was the context of the time. If you were lucky enough to get it, why would you say no?”

The same was true even in the midst of the storm. As they prepared to play Wexford again in a contest they would win by 13 points, former Cork captain Alan Browne recalls a sense of amusement at the entire affair.

“As far as I recall, it was a good distraction really. I can’t remember any player having any issue with Seán Óg in relation to him getting a deal. The attitude was more luck to him.” That was particularly important for the Blackrock man. A year previous was the infamous league final between Cork and Kilkenny. There was a pre-match protest where certain players tucked their shirts out and wore their socks down for the parade. Initially, the plan was to opt out of the team photo. Browne wasn’t in favour of that and made his feelings known.

“There was a lot of members of the Cork team who were not members of the GPA. I wasn’t a member, but a group came back and said this is what is happening.

“Look I wasn’t happy as a senior player. That was a young squad and it’d be a big distraction. I said if you want to do something, pull your socks down and jerseys out. Whoever was in favour could do it and it wouldn’t be a major deal. That was an inhouse decision. Kilkenny had said they would follow suit… I was disappointed with it all. It was a distraction and we lost by a point.” In his mind the lines of demarcation are clear. Throughout history deals were always done. Better it be public and legitimate rather than covertly or to the harm of the association.

“Why can’t a player benefit from their profile? Before it was about getting jobs as sale reps and banks. Now that is not the case. I know some employers don’t want GAA players because they can’t work certain hours. Also, as long as it is commercial. I didn’t like to see lads anywhere taking quid to present medals or go to a club. Don’t take it out of the game. But generally, if someone wants to use their profile for commercial benefit, why not?”

In time there would be more chapters in this ongoing story. Players developed the confidence to stand up and use their voice. Soon after the GPA gained recognition and after that control of their member’s image rights. 20 years ago, those players intentionally took a huge step into a new landscape. There was no going back.