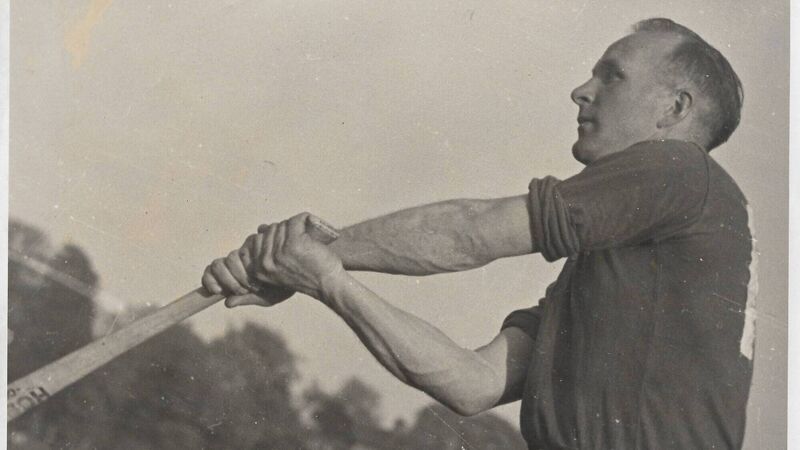

Christy Ring through the eyes of those who marked him: 'No matter what way you played on him, he’d make you famous'

Christy Ring

You could say Christy Ring baptised Matt Hassett as a championship hurler.

“I suppose people were wondering where they found me,” Hassett laughs. “And I suppose after I marked Ring the first year, with not too much damage done, I was sort of accepted. I held my place, anyhow, for a couple of years. I wasn’t a Tipp star, or ever going to be a Tipp star. But I held on.”