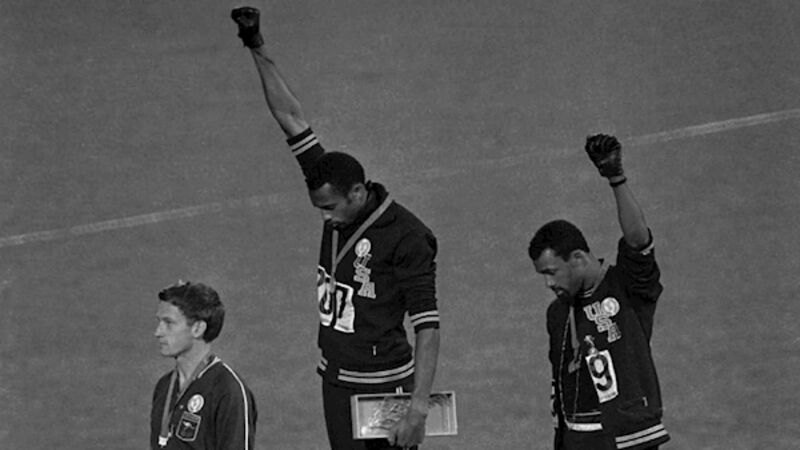

Three men, two gloves and one powerful sporting moment

Fifty years ago today, on October 16, 1968, one of the most powerful political protests of modern times, and certainly the most famous using the vehicle of sport, took place at the Mexico City Olympics.

It involved three men, though one of them is often ignored in the history books, and two black gloves, writes