Enda McEvoy: Like the granny rule, Pogues' 'Rum' redefined what it meant to be Irish

FIESTA: The Pogues in the mid 80s.

Memories of the summer of 40 years ago…

The rain (ceaseless). Live Aid at Wembley (I wasn’t there). U2 at Croke Park (I was). Getting a loan of Pat Carroll’s copy of Murmur, REM’s debut album (they’d been on the bill at Croke Park), and finding it intriguing if utterly unintelligible lyrically. What in the name of God was the lead singer – Michael Somethingorother; Stripe? – muttering about?

Then came the first week in August. After lunch on the Wednesday I popped into Sherwoods in High Street, bought Rum Sodomy and the Lash on LP and hauled it back to the newsroom, where they were all enquiries about the contents of the bag. It went onto the record player as soon as I got home. It stayed there, or at any rate within six inches of the turntable, for years.

My knowledge of the Pogues dated back to the previous February. I’d caught the train home from college one Friday afternoon and a bunch of lads I knew hopped on in Carlow, all chat about a gig by some London-Irish band there the night before that had allegedly been absolute mayhem. They weren’t exaggerating; James Fearnley would say the same in his memoir . The Boys from the County Hell indeed.

Curiosity led me to get hold of their album Red Roses for Me. It introduced new people with strange sobriquets who soon became acquaintances – Maestro Jimmy Fearnley, Country Jem Finer, Rocky O’Riordan, Andrew the Clobberer Ranken – and it pulsed with the shock of the new. This was the bastard child of Irish trad music and punk; it clattered along at 100 miles an hour, visceral and exhilarating and full of swearing; and the lead singer was a harmless looking lad with terrible teeth, the kind of person who was surely destined to live at 200 miles an hour and to die young.

As opposed to being, say, the kind of person who’d winkle his way into the public consciousness to such an extent as to become a national treasure whose funeral many years later – yes, he stayed the course to an improbable degree - would be broadcast live on BBC and Sky News.

I couldn’t wait for the follow-up in August.

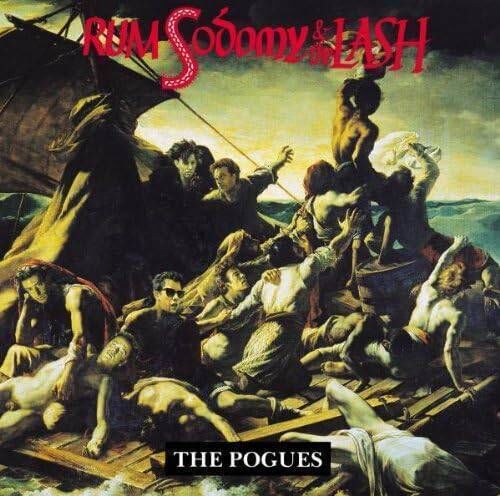

The cover of same was arresting, an old painting of a shipwreck with the faces of the band members superimposed on the survivors, and there were 12 tracks. Shane MacGowan, the harmless looking lad, had a hand in half of them. The other half included old standards reworked, an instrumental and the Pogues’ take on Ewan MacColl’s Dirty Old Town and Eric Bogle’s And the Band Played Waltzing Matilda.

The album was produced by Elvis Costello, who correctly decided his task was “to capture them in their dilapidated glory before some more professional producer fucked them up”. He succeeded admirably. The finished product was eclectic but coherent, smoother around the edges than its predecessor but still rambunctious, and it didn’t outstay its welcome. Forty years later it sounds as fresh, urgent and compelling as it did then.

Its cast of characters was colourful and sprawling. McCormack and Richard Tauber, whoever he was. Men you didn’t meet every day. Billy Bones, who knew an Arsenal from a Tottenham blue. Irish navvies. Anzac soldiers. O brave new world, that has such people in it!

The Sick Bed of Cuchulainn, composed under the influence of heaven knows what refreshment, whooshed out of the speakers. Glasses of punch, angels and devils, Frankfurt and Cologne, rattling death trains, the Euston Tavern. Any mention of midnight Mass among my circle has ever since produced a predictable but somehow comforting gag about dropping a button in the plate. It remains an astonishing song and, at the risk of sounding like a Nick Hornby character, one of the all-time great opening tracks, right up there with Seven Nation Army and Whole Lotta Love. It could only be the work of MacGowan.

Sally MacLennane was another barnburner. A Pair of Brown Eyes was beautiful and depressing in fairly equal measure. The Old Main Drag, about a down and out doing unspeakable things in London, sounded uncomfortably autobiographical. Most of the remaining tracks were random but somehow fitted together and made sense.

I was instantly and totally charmed. I went as far as investing in a black Rum Sodomy and the Lash t-shirt (someone lent me 10 pounds). Just for the sake of it, I enquired of my siblings the other day what they’d made of the album at the time.

Pepsi Sister. “The energy and the incorporation of traditional Irish music was nothing I’d heard before. The storytelling: the songs were brimming with detail, raw emotions and the underbelly of life. Some of the band, obviously MacGowan most notably, were the children of emigrants who were celebrating their Irishness – and pride in one’s Irishness was something that was in short supply here at the time. In a sense they gave licence for their fans to be proud of their music and history and to define a new version of Irishness, different from the Dev version.”

Archive Sister, a pre-teen, was more struck by the bold words. “’Frank Ryan bought you whiskey in a brothel in Madrid’ – what was a brothel? I’d never heard the word before.”

The album even managed to expand one’s cultural horizons. Kind of. In July 1987 myself and two college friends spent ten days in Paris around the time Stephen Roche won the Tour de France. The afternoon we went to the Louvre we made a beeline for Gericault’s Raft of the Medusa, the inspiration for that cover, to pay due obeisance. In another room there was a much smaller portrait of some moany woman called Lisa. We were considerably less impressed.

For the next few years the Pogues were a force of nature. Small but perfectly formed, the Poguetry in Motion EP in the spring of 1986 would constitute the band’s finest moment pound for pound. (I’d never have believed that A Rainy Night in Soho would be chosen for so many wedding first dances.) If I Should Fall from Grace with God was their best album, Love and Peace was all over the place, Hell’s Ditch melodic but meh.

Yet there was more to them than simply the music. Almost despite themselves they precipitated a discussion about Irishness: what constitutes it, who it encompasses, who is entitled to claim it. The actress Anne Marie Duff has remarked about how, as a child of immigrants in the 1980s, the Pogues meant so much to her “before being Irish was fashionable” – and being Irish in 1980s England was anything but fashionable. At Euro 88 and Italia 90 it was they and U2 who provided the soundtrack for the Green Army, a noticeable cohort of whom were second-generation Irish.

But here’s the kicker. If MacGowan was Finer and Fearnley and Ranken were about as Irish as guacamole. Fearnley’s father, indeed, was reflexively anti-Irish. When Ireland beat England in Stuttgart they did so with a starting XI containing two London-born players, two Yorkshire men, a Glaswegian, a Scouser and – of all things - a Cornish man.

Digressing only slightly, I’m currently stuck in Great Hatred, Ronan McGreevy’s tremendous book on the 1922 murder in London of Henry Wilson: fine soldier, repulsive old imperialist and a Longford man. The killers, Reggie Dunne and Joe O’Sullivan, were Londoners. In passing, McGreevy mentions the Tebbit Test; we can safely say Reggie and Joe would have failed it spectacularly.

Ed Sheeran, who turned up at the Fleadh Cheoil in his father’s native Wexford last weekend, recently described himself as “culturally Irish” – certainly the most interesting thing he’s ever said or written. There are all sorts of shadings and nuances here. The conversation will continue indefinitely, perhaps eternally.

One of the very best Pogues gigs I saw, incidentally, was in a sparsely attended Bridge Hotel in Waterford the night Gary Mackay’s goal in Sofia sent Ireland through to Germany. “This one’s for Scotland,” MacGowan slurred.

No less memorable was the concert at the Point a couple of nights before Christmas the following year. At the end of proceedings, having lost a shoe in the mosh pit, a chap called Brian Phelan grabbed an armful of loose shoes off the floor at the front of the stage and tried them on in the car on the way home. Not one of them fitted. My fellow passengers amused themselves by pelting me with them as I got out afterwards. My mother’s mystification next morning at the amount of footwear inexplicably strewn outside the front door may easily be imagined.

The years went by and times they changed. The drawback to joining a band on the ground floor and taking the lift up with them is that other people get in along the way. Latecomers. Arrivistes. Bandwagon jumpers. People under the impression that the Pogues are only Fairytale of New York. The wake scene in that episode of The Wire destroyed Body of an American for me forever. Bastards.

Peace came dropping slow. Eventually I generously concluded, albeit not before a terrific mental struggle, that the more people – as opposed to the fewer people - who listened to the Pogues, the better. It can only be their gain.

Has there ever been a more beautiful ballad than Lullaby of London? Not unless it’s Misty Morning Albert Bridge - and yes, I the latter is a Finer opus. Irritatingly but predictably, most of the tributes following MacGowan’s death overlooked the reality that his plangent stuff was far more powerful than his punky stuff. Nor is it every band who could come up with one track about Cheltenham and another about greyhound racing, so further kudos to them on that count.

If there was a proto-MacGowan it was James Clarence Mangan, the man hailed as Ireland’s first national poet and a similar hardcore troubadour. Mangan was opium-addled; the contemporary MacGowan would have been a terrible man for the laudanum. Not that that’s the only parallel; what is Mangan’s “There’s wine from the royal Pope”, after all, but the great-grandad of MacGowan’s “Spanish wine from far away”?

Both men eventually and inevitably succumbed to their addictions, although I do like to think that when they shoved MacGowan in the ground, in some parallel universe he stuck his head back out and said, “We’ll have another round.” Ireland’s latest national poet.

Life came along and times kept changing. Sherwoods gave up doing records long ago; these days they’re out on a business estate. My t-shirt fell to pieces through overuse; I bought a replacement, in khaki because black was unavailable, a couple of years back.

But Rum Sodomy and the Lash endures and always will. Billy is still running around with the rare old crew. The empire is deep in darkness but the railway’s there yet. And McCormack and Richard Tauber – an Austrian tenor, it transpired - are singing by the bed, now and in time to be, and there’s an angel at Shane MacGowan’s head.