Paul Rouse: every club is unique. What makes one great?

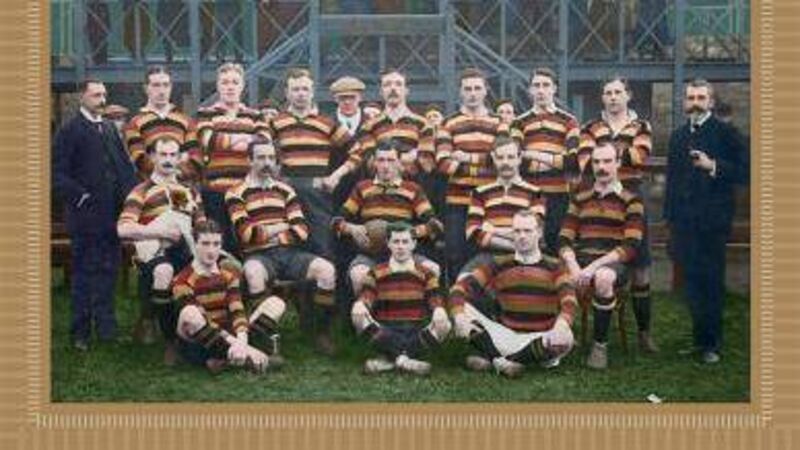

Lansdowne FC: A history, by Ivar McGrath.

It is true that every club is unique. What makes each unique, of course, is the people who walk through its doors and wear its jersey and watch its matches and do all the many jobs that allow a club to function year after year and, of course, socialise together.

It is these things that create the meaning of a club and allow that club to continue across the generations.