Different class: The role of social standing in Irish sport

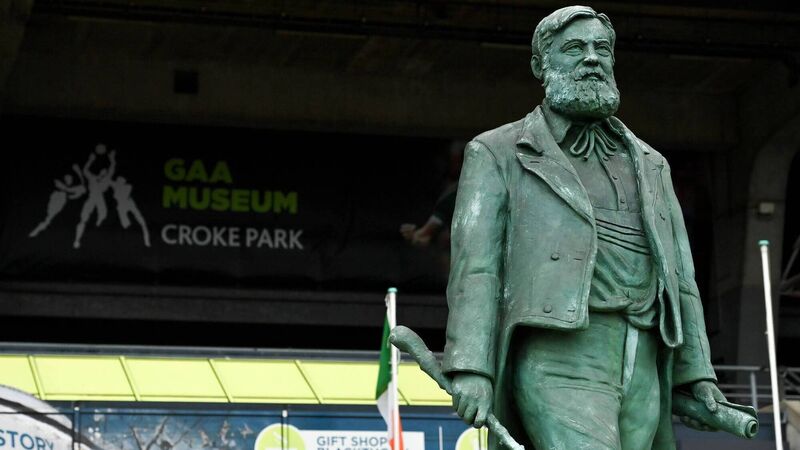

A statue of Michael Cusack, who founded the GAA partly out of disgust at what he saw as the exclusionary nature of Dublin athletics. Picture: Brendan Moran/Sportsfile

Wealth and class have a profound influence on sporting involvement in Ireland. The first sporting clubs based in Ireland were the preserve of the ascendancy and middle class. This began with the Royal Cork Yacht Club, founded in 1720, and continued through the remainder of the eighteenth century with the establishment of clubs for hunting and horseracing.

Later, as the Irish middle classes grew in the nineteenth, an alliance of blood, land and commerce was forged in rugby, tennis and golf clubs in the growing suburbs where money found money.