Eimear Ryan: If you have never been humbled in your career, how do you accept its end?

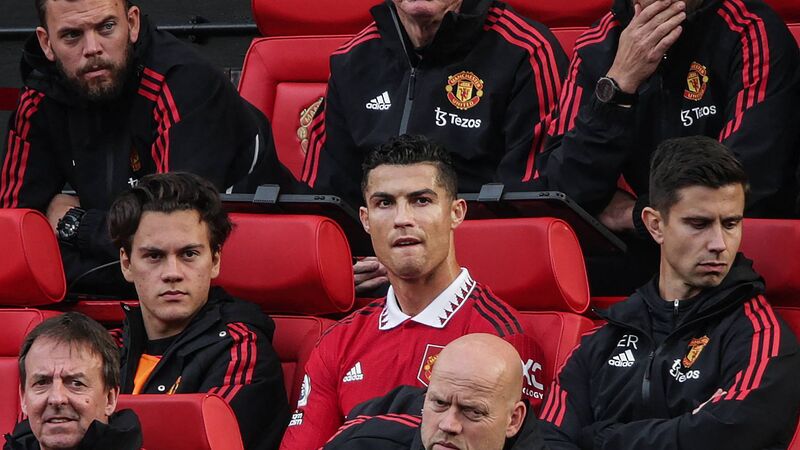

Manchester United's Portuguese striker Cristiano Ronaldo sits on the bench There is no Junior B option for him. (Photo by IAN HODGSON/AFP via Getty Images)

Bowing out gracefully: it’s an artform. Whether it’s in work, sport or (whisper it) politics, picking the right time to depart the stage is never an easy decision. You need to have enough humility to know the jig is up, but enough pride to do it in the most flattering way possible. You want to stomp off the stage, not quietly slink. Most importantly, you want to leave with your reputation intact, while knowing you still left it all on the pitch.

All of which to say, I have some sympathy for Ronaldo’s current predicament in his standoff with Man Utd manager Erik ten Hag. (Yes, Ronaldo – multi, multi-millionaire, more Instagram brand than human, more icon than player.) His relentless pursuit of, and prioritisation of, individual greatness within a team sport has served him well in his career, but ageing on a team inevitably means shifting to a supporting role – something he is temperamentally unprepared for. (As anyone who’s ever sat on a sub bench knows, it can be hard to take when the team does brilliantly without you.)